Summary:

- The "die with zero" philosophy encourages spending earlier in life, prioritising meaningful experiences and timely giving to loved ones rather than deferring enjoyment or leaving large inheritances till too late.

- It promotes intentional financial planning – using “time buckets,” avoiding regret, defining what is “enough,” and reducing fear-driven over-saving – but assumes stable income, buffers, and no major financial shocks.

- While thought-provoking, the approach can be risky in high-cost environments like Singapore, where longevity, rising healthcare expenses, and the need for financial security may limit how fully most people can adopt it.

Before we get into the nitty gritty of the concept of “die with zero”, here’s a preamble to set the stage.

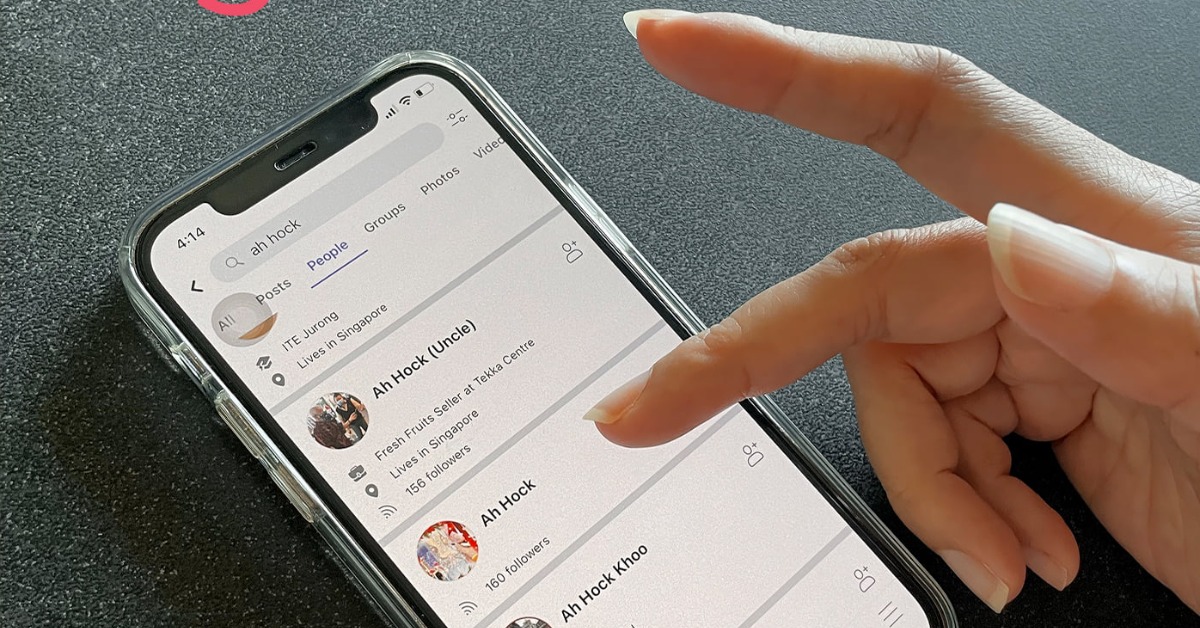

In a July article on Estate Planning, I told the story of a 67-year-old single friend who wanted to give away $600,000 to his niece, the one person who mattered to him, so that she could pay off her mortgage and therefore be free from debt at an early age.

This way, I don't have to worry about any squabbles over my estate when I pass away because the person I really want to benefit has already benefitted.

As he said,

A month earlier before that, I had written about decumulating, i.e. spending your savings in retirement.

Coincidentally, a few months later, I came across an interesting book by a writer named Bill Perkins titled Die with Zero: Getting All You Can from Your Money and Your Life. It incorporates both ideas that I had written about – spending your money after giving away as much as possible to whoever matters.

A common-sense guide to living rich . . . instead of dying rich. Imagine if by the time you died, you did everything you were told to. You worked hard, saved your money, and looked forward to financial freedom when you retired. The only thing you wasted along the way was . . . your life.

Here's the book’s synopsis:

Perkins’ core message is to spend your money in ways that generate lasting memories and fulfilment (or as he calls it, making “memory dividends”).

Advertisement

Main missive of "die with zero"

Many people delay enjoyment until retirement – which is sometimes too late. His approach encourages intentional living and intentional giving rather than deferring joy or meaningful activities.

Here are some of the main points made in the book:

1. Make use of “time buckets”

The book argues that certain experiences are age-dependent – what you can enjoy at 35 may not be possible at 75. Thinking in

“time buckets” helps you match your resources to the phases of life when you can get the most out of them.

2. Reduced regret later in life

People often regret what they didn’t do – trips postponed, passions shelved, dreams delayed. Perkins’s philosophy pushes you to avoid this common regret pattern.

3. Giving your money to loved ones (when it matters most)

Instead of leaving a large inheritance when you die, Perkins suggests giving money to loved ones when they can use it most – often in their 20s–40s. This can have more impact than receiving it late in life.

If you’ve read my article on Estate Planning which I mentioned earlier, this was exactly my friend’s motivation when he gave away the $600,000 to his niece.

A side note on gifting. Physical items like jewellery and other valuables can be gifted by delivery, i.e. by handing it over to the recipient. However, for avoidance of all doubt (and future disputes), a Deed of Gift could be drawn up and properly witnessed to prove evidence of the gift.

For a Deed of Gift, there are certain legalities to observe, such as the donor (person giving the gift) being of sound mind. This means that they understand what is being given away, to whom, and the consequences (e.g. loss of ownership) of the gift being given away.

The Deed must specify with legal clarity what is being gifted, to whom, and the date when it transfers. Note also that a Deed of Gift is gratuitous – there must be no payment by the recipient. If money is exchanged, it becomes a sale or contract, not a gift.

There are various other ways gifting can be done. Instead of a lump-sum gift, you can support your chosen beneficiaries by:

- Paying for their or their children’s tuition;

- Funding professional courses;

- Paying for a downpayment for their home;

- Covering caregiving or medical expenses;

- Helping them on their entrepreneurial journey to start a business.

Alternatively, you can structure payments to occur only when certain life events happen, such as marriage, having a child, completing a degree, or reaching a specified age.

It’s best to consult a lawyer on the best way to do this (e.g. either through a trust or private contract).

4. Smarter financial planning

Next, Perkins’ system encourages thinking intentionally about:

- How much is "enough"

- When you're likely to spend more versus less

- How to avoid over-saving

Arguably, this can lead to a more efficient and thoughtful use of money over the course of a lifetime.

5. Encourages letting go of fear-based saving

Many people save excessively because of worst-case-scenario anxiety. Perkins argues for reasonable buffers rather than hoarding, which can free you from overly conservative financial behaviour.

Theory versus reality

Now, all of the above points are fine – in theory.

In case you’re wondering about Bill Perkins and how he could recommend spending such a large portion of your money before you die, it’s worth knowing that he’s a hedge fund manager, which suggests that he’s much richer than the average person and therefore much better placed than most people to maybe retire early and spend his savings on enjoying life by making memories.

The biggest risk in adhering to his advice is that you could run out of money in old age, a period of life when earning capacity is limited. As we all know, Singaporeans are all living longer, so longevity risk is real – especially as medical costs rise.

Singapore's high cost of living

Singapore’s high living costs – especially in areas regarding housing, healthcare, childcare, and transport – mean outliving your money is a bigger risk when compared to other countries. Planning early-life spending helps avoid excessive saving driven by fear, but Singaporeans still need larger buffers.

To some extent, CPF LIFE mitigates this risk, but for most people, the monthly payments would cover only their basic needs. What if money is needed for an emergency?

Healthcare inflation is a major concern. Healthcare in Singapore may be excellent, but it’s costly. Long-term care at public institutions can exceed $2,000–$4,000/month while private care can cost much more. A large medical buffer is therefore essential.

Also read:

I’m Not Ready To Die: Living Life To The Fullest In Your Silver Years

74-year-old author Josephine Chia reflects on life and the attitude she upholds as lives through her silver years.

“If I Can, If They Still Want Me, I’ll Continue To Work”: KKH’s Oldest Midwife Reflects On Former Hospital Being Gazetted As National Monument

82-year-old Too Ah Kim isn’t just KKH’s oldest active midwife – she’s also a living part of its history.

"Die with zero" can be overly optimistic

The book implicitly assumes stable income, ability to invest, a financial buffer, and no major shocks. For those living paycheck to paycheck, or are supporting ageing parents and several children, the framework becomes harder to apply.

It also underestimates the psychological comfort gained from having savings. For many, a large savings buffer provides emotional security. Perkins’ approach reduces that buffer, which can increase stress in some rather than reduce it.

The bottom line

“Die with zero” as a concept is best used as a philosophical, thought-provoking guide, not a strict formula. It encourages spending earlier on in life on meaningful experiences, avoiding hoarding out of fear, and giving to loved ones when it has the greatest impact.

But following it too rigidly carries risks, especially regarding longevity, healthcare costs, and financial obligations.

At the end of the day, whether you can afford to follow the ideas Perkins has laid out depends heavily on your own individual circumstance.