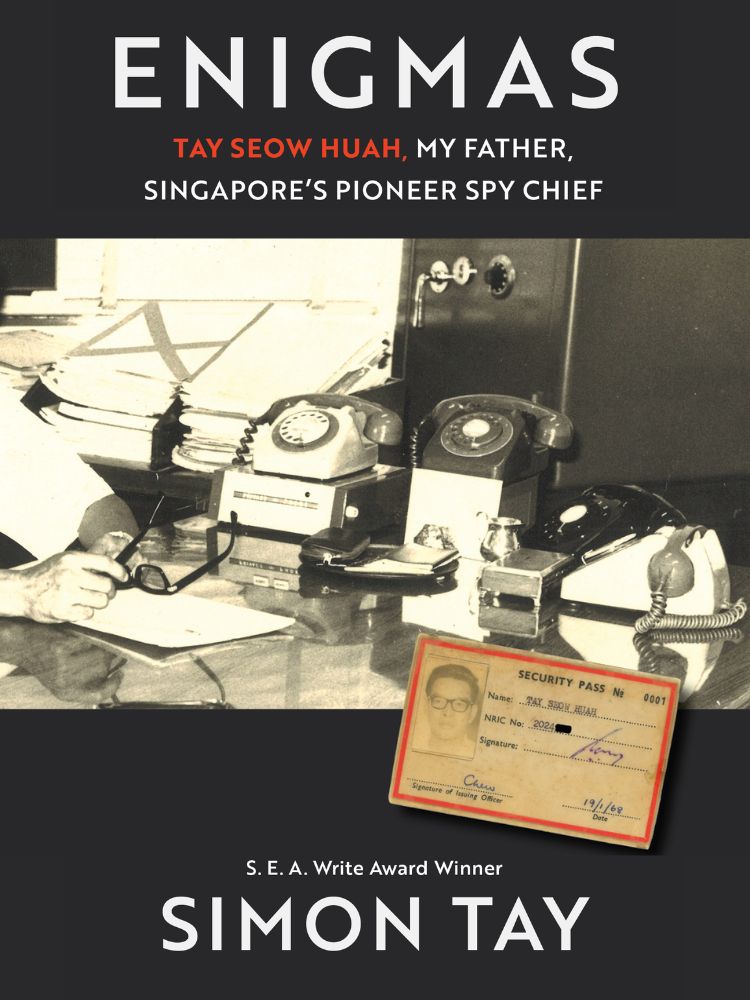

Credit: Landmark Books

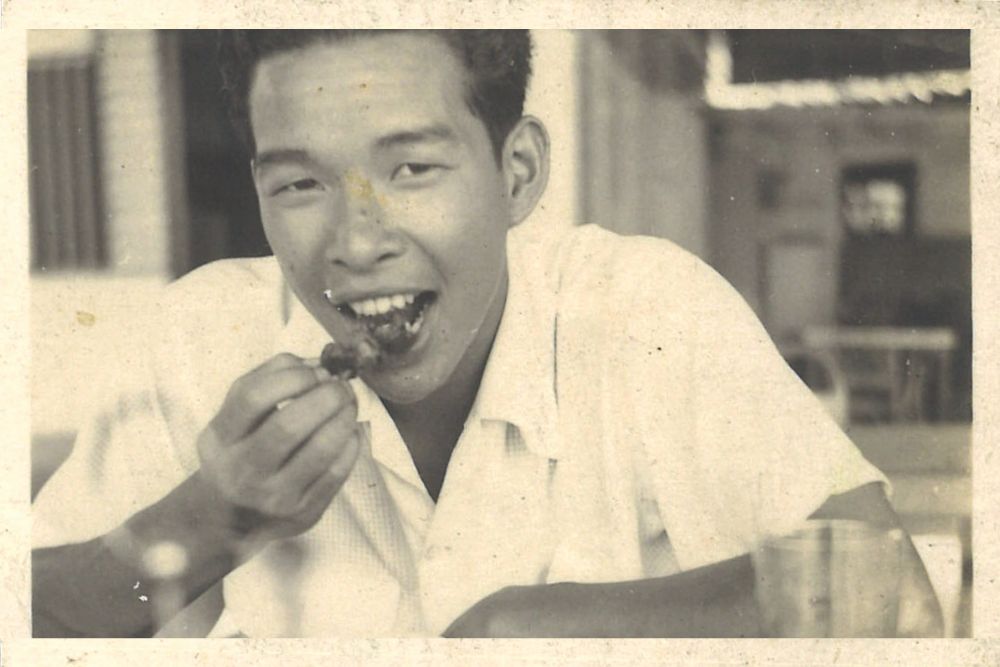

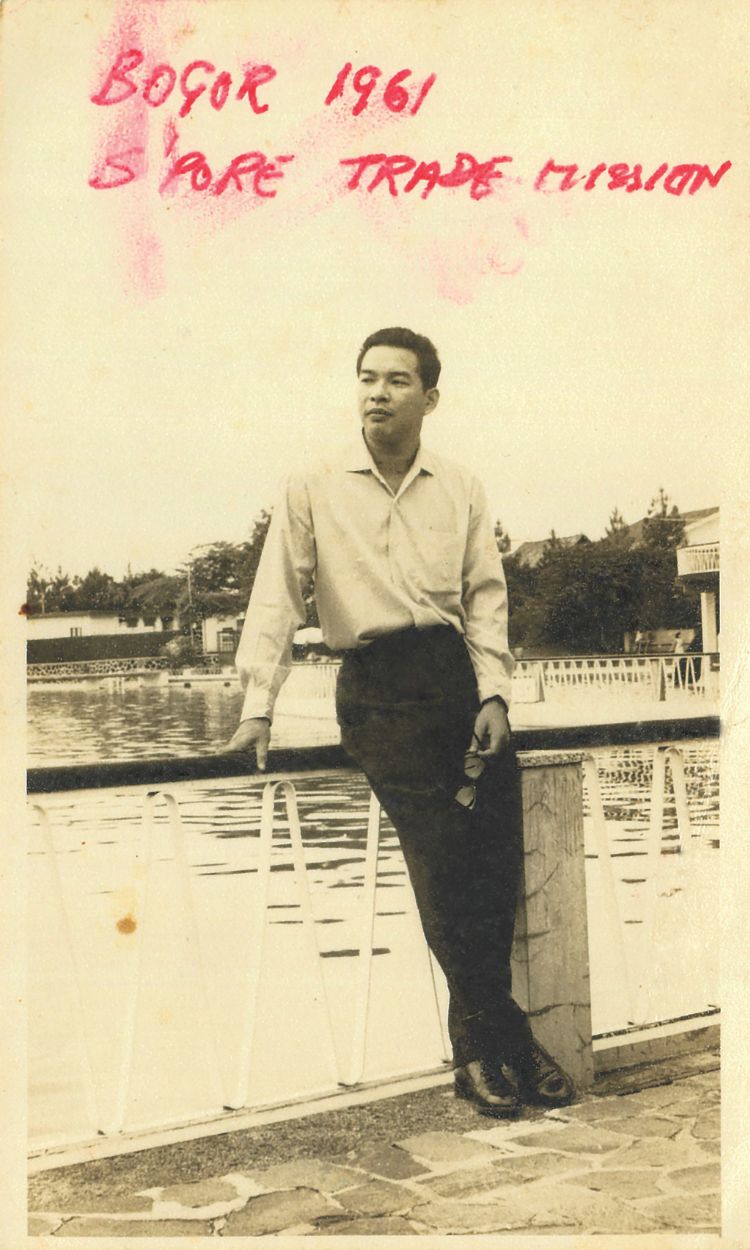

Simon Tay: I was 13 when my father suffered a massive heart attack and 19 when he died. But it was only during the pandemic that I began writing about his life and work. This book, Enigmas: Tay Seow Huah, Singapore’s Pioneer Spy Chief was published earlier this year.

Why did I take so long, some asked. There are reasons but, in consequence, I have written with a perspective that would have been impossible earlier. But now in my 60s, I intuit the beginning of the end in my own work and life and find empathy with my father.

His end was abrupt, and two-fold.

The heart attack came in 1974 and struck him some six months after he had coordinated the government response to a terrorist attack. Dubbed the Laju Incident, the attackers set off bombs on the Bukom oil refinery and then tried to escape aboard a small ferry, with hostages held at gun point. The tense stand-off lasted more than a week, reported in global newspapers and television, and connected to a global wave of bombings and airplane hijackings in that era.

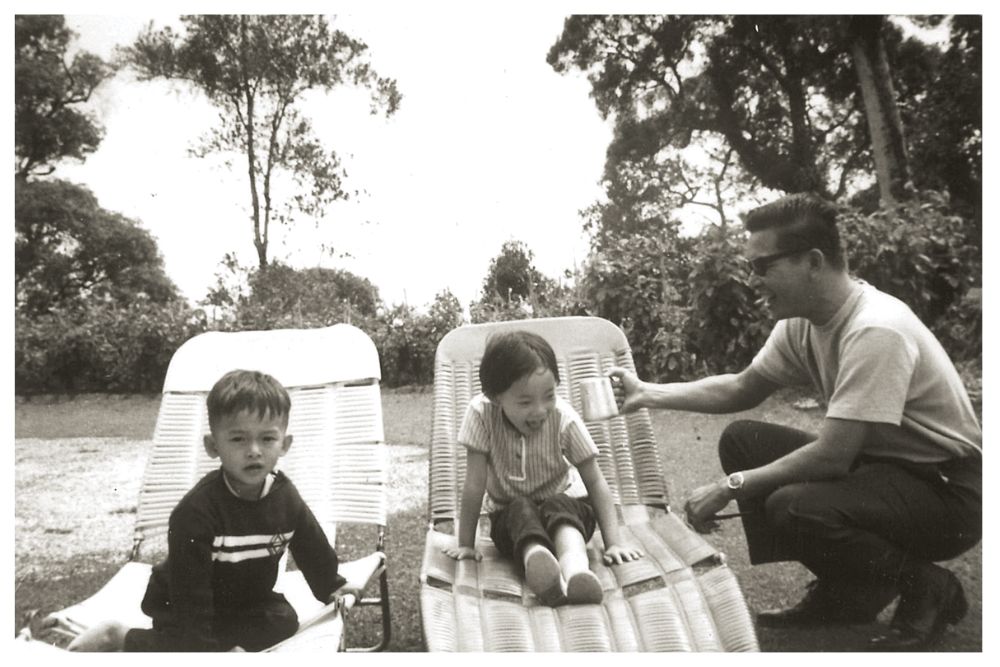

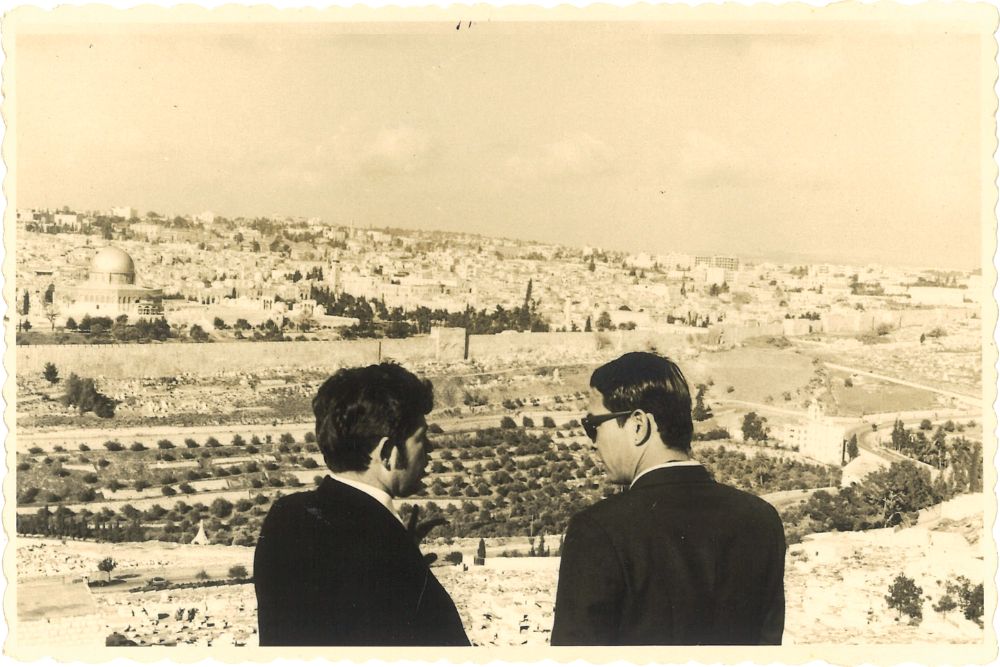

Over the preceding decade, my father had started and directed the newly independent Singapore’s security agencies. He enjoyed the work but its pressures were a factor in his sudden and major heart attack. Surgery in the USA followed and he survived, but his health and stamina were never the same. Within 18 months, following a medical board examination, he was retired prematurely from government.

Advertisement

My father lived only five years more. A scan showed another major problem, what seemed a tumor at the stem of his brain. During surgery in London, the further shock was that the problem was instead a mass of aneurisms. He never regained consciousness.

His setbacks in health and career occurred in his early 40s, and he died aged only 47. But my father’s story was not only about illness and death. Writing Enigmas, I realised it is, more importantly, also about life and purpose.

In his last years, my father was recovering and trying to forge a new, second life. He was walking through dark woods in which there were moments of dappled sunlight. Lessons can be taken.

Dark wood – loss of purpose

Disaster can come to any one of us in our lives, at any time. One of the most poetic warnings is from the Italian poet Dante’s classic poem, Inferno, and its opening line, “In the middle of our life’s journey, I found myself in a dark wood.”

The poet’s midlife setback was caused by political in-fighting. When his faction lost and he was exiled from his city and all he knew, entering the “dark wood”. For my father, the cause was a heart attack.

Today, there are many causes for such fortune reversals that we can face in our career: retrenchments and job dislocations are now commonplace, and can be especially exacting on those in middle to senior management.

The first instinct is to seek re-employment – with the same sort of job in another company at hopefully an equivalent wage. But for seniors, lateral moves can be challenging. Not all succeed and, stymied, we can react with denial, blame and bitterness.

My father was unprepared for early retirement. It was not just the pay – in those years the salary of even senior civil servants was low. Nor was it the occasional pomp and ceremony in his job. There was the loss of the sense of purpose. He had given so much of his focus, energy and time, to a cause he felt was important. What he did had become part of his identity.

This is true too for many of us. We may complain about work and wish for time to do other things. But most also underestimate how much work is part of our lives, until it is no longer there. Some may not find alternatives.

In writing about my father, my research touched upon another life. Professor Wong Lin Ken had served as Singapore’s first ambassador to the USA and then, after winning a seat in the 1968 elections, was appointed Minister. Yet after just two years, Prof Wong stepped down and returned to the university.

My father had worked with him in government, and they met again in the university history department; Prof Wong was the head and my father a visiting fellow.

Teaching after such high profile and urgent work, my father chaffed. He used the time to rest and recover. For Prof Wong, while in charge of the department, he must have felt dissatisfaction too. The former minister suffered depression and tragically committed suicide in early 1983, age 52.

When our careers end and our purpose is gone, some can find ourselves lost in especially dark parts of the woods. We should not underestimate the real effort to find a path to a better, safer place.

Paths of Dappled Sunlight – finding a new identity

There are things that my father did to cope, adjust and move forward. He put aside regret to re-evaluate what he had and what he needed. He re-orientated and sought other and different things.

After university, he was appointed executive director of the Singapore Manufacturing Association, then the main business chamber. It was a change. No longer in government but connected to business. Not focused on security while relating to international trade and investment. He liked that there were familiar things, but also new elements.

In his personal life too, things were new. He lived more simply and also more freely, putting aside old routines and embracing new activities. He tried stretching and yoga (then a rare thing). Rather than speed boats and competitive sports, he took up sailing with the wind in the sails. He gave more time to old pursuits like classical music and reading.

Not all changes were benign. Differences in his marriage had emerged over the years, and my father made the decision to move away from our home and live on his own. This was difficult for both him and my mother, and all the children.

A perspective 50 years in the making

I now understand that my father was only trying to sort out his own life. But in those years, I did not have that understanding. In this period of separation — with his life changes and my teenage angst — our conversations were not always easy or comforting.

Yet my father would always make the effort to meet and talk. He had promised, when I was a child and he had been going full speed at work, to spend more time with me as I grew. He kept that promise. For me, I will never forget those times, and Enigmas closes with our conversations re-imagined.

My father put aside regret and found balance and a good measure of satisfaction in his last years. When he left for that final operation, he knew the risks and faced them with equanimity and a good measure of grace.

From his last years, I internalised the following learnings.

There will come changes that we do not choose but must learn to accept. There are other changes we seek and should undertake, whether they are lifestyle or more fundamental to our lives and those around us. There are ambitions and conventions to shed. But there are also promises to keep.

As we search for our path, we can encounter stretches through the woods where a deep darkness gathers. Yet there can also be hope and memorable instances of joy and connection, dappled spells of light that guide and lead us on.

Credit: Landmark Books

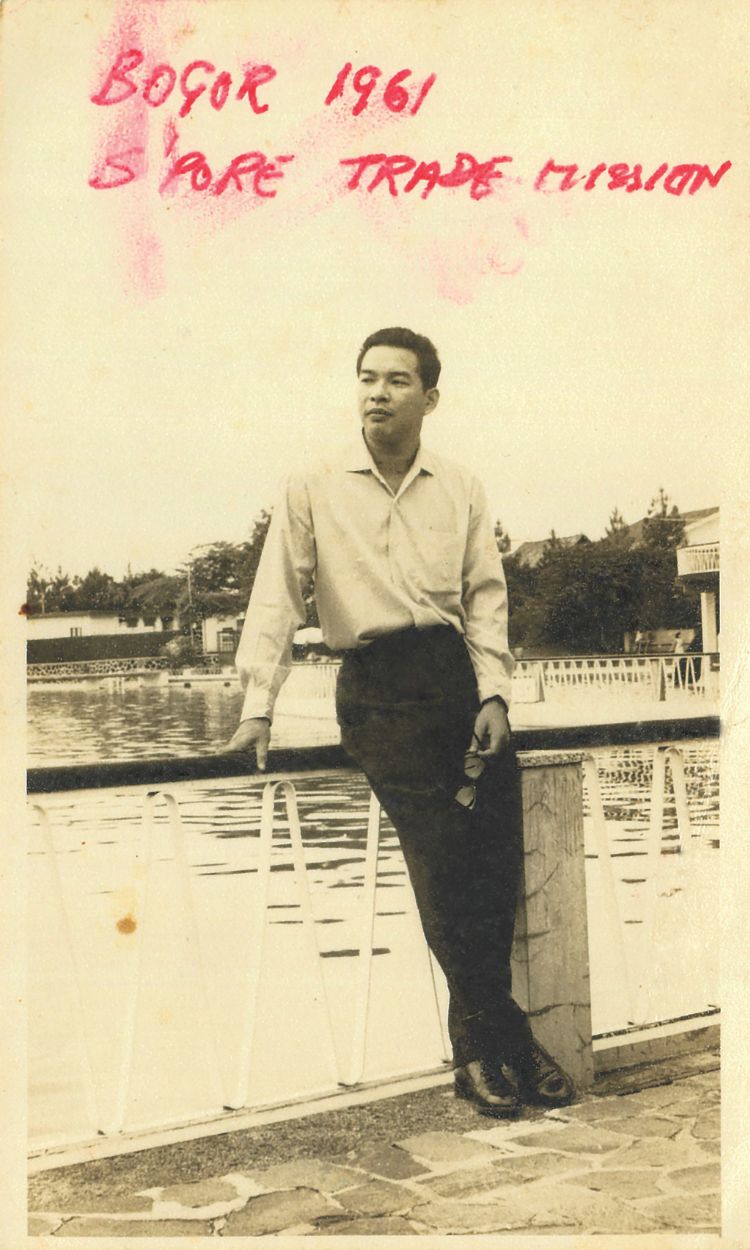

Credit: Landmark Books

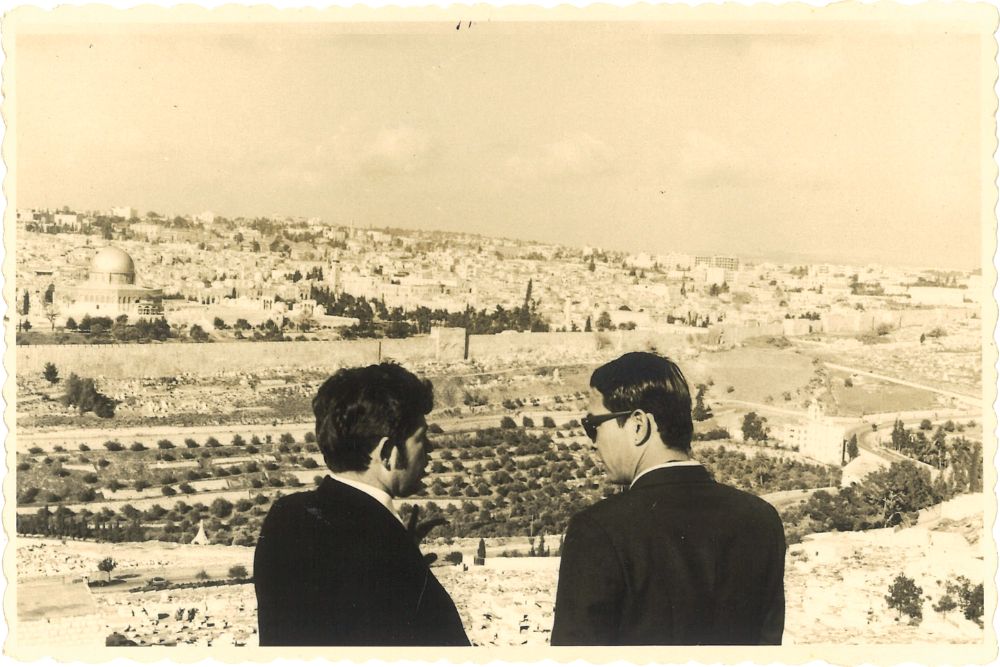

Credit: Landmark Books

Simon Tay is an award-winning author. His 2024 book is Enigmas: Tay Seow Huah, my father Singapore’s pioneer spy chief. It is available here.