A vignette by Jasmine Adams

“Mam, freezer very empty, next week cook what ?” Alice, my ever efficient and competent Filipina help of nineteen years, shrilled into my mobile.

“OK, later, I have half an hour between breakfast meeting and lunch. Meet you at Freezer Mart at 11.30, bring trolley.”

“Mam, what soup for Sir? Pumpkin, mushroom? Last time, seafood bisque, he complained it was very fishy.” Alice’s all too honest but well meaning frankness combined with the robotic lift, drop and pay motions in the supermarket stroked a guilty chord in me. My marketing list included fish bleached white in their shrink wrapped tightness, bacon, back and streaky, fat evenly distributed and rectangles of speckled brown mince, a neat 250 grams each, ready to be dumped into a bolognaise sauce.

Confronted with wall to wall shelves of food at FM, I suddenly recalled how different marketing days were with grandmother when I was growing up in a shophouse at Marshall Road.

Advertisement

Countless varieties of meatballs laid out in the chiller vied for my attention, not for their produce, but impressive photography of perfect symmetry and the right degree of golden brownness.

I sensed grandmother telling me, “Chwee, don’t anyhow buy, make them yourself lah.”

Grandmother’s even, firm, but non accusatory tone echoed in my head and brought me back to when I was six, just as Singapore was clamouring for independence from British colonial rule in the 1950s. Everything then was made by Grandmother from slabs of carefully selected cuts with the right proportion of fat to lean, chopped into a pasty mixture and hand shaped into imperfect balls.

Stock from soup was came from her pots and not in packs or cubes which I sneakily purchased.

Grandmother did not own a fridge until I was about ten years old, so marketing was a daily affair for her. She took me along, ‘to prepare me to run my own home when I get married’ she said. We did our marketing at Katong Market which was close by.

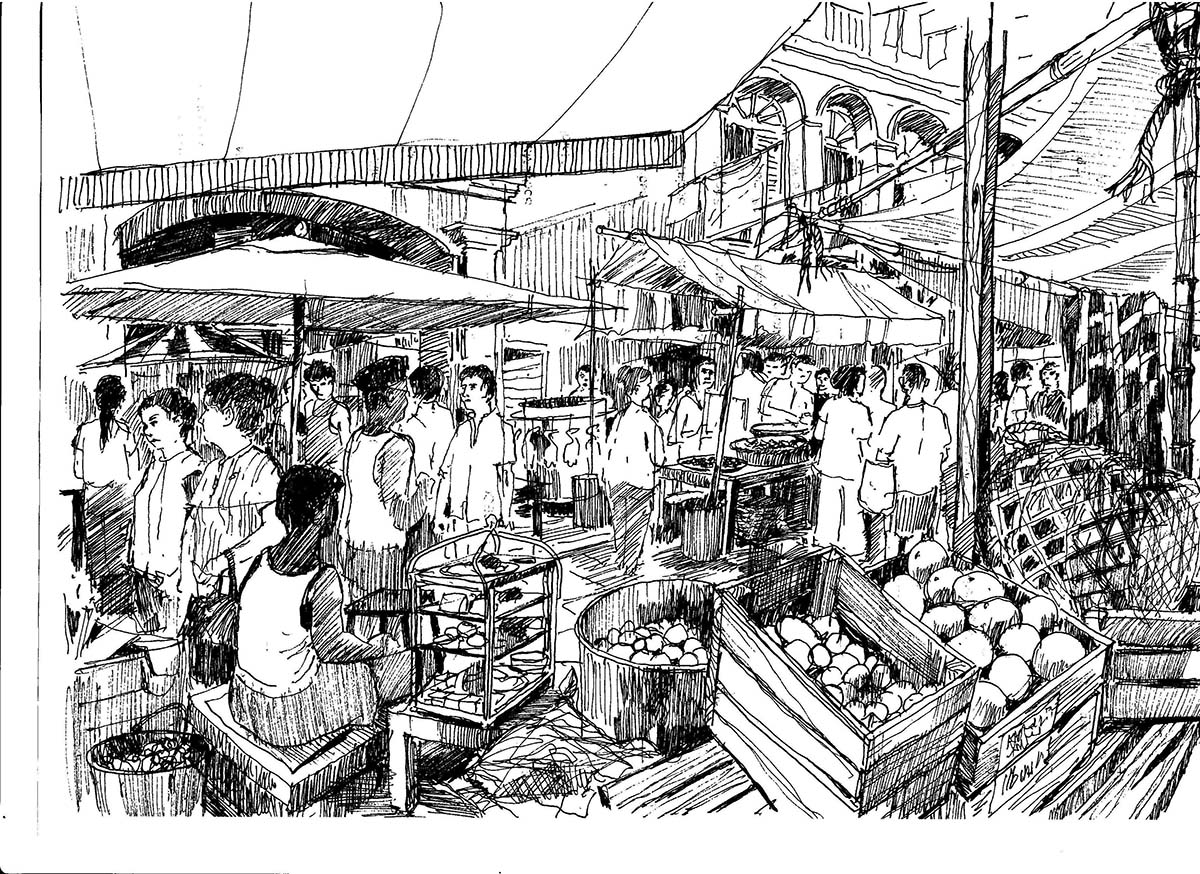

Shop vendors and hawkers had their privately owned space on which they set up makeshift stalls with ramshackle coverings. Supporting poles doubled as demarcations and each stallholder tried to maximise his storage cum display areas. The pedestrian pathway between each set of roughly parallel rows weaved a zigzag of a maze that could barely accommodate two housewives with their rattan marketing baskets.

I hated it when grandmother lingered at every stall to inspect the produce. Her parrying with the green grocers, sundry shops resulted in my being shoved every which way by impatient housewives. Often I found myself plastered against wet and pickled vegetables and all manner of damp and soggy goods. Stallholders yelled at me for ‘stealing’ their produce as slimy green cabbage hijacked a ride on my thin cotton pyjamas and bean sprout casings encrusted themselves on m flapping sleeves.

Mother hated grandmother taking me to the market. She insisted my place was at the study desk reading story books, doing Maths and practising my writing, and be a pretty little girl in frilly dresses with ribbons and not go to market in pyjamas.

Of course mother ‘lost’ her arguments. Father said these were ‘women’s matters’ and not for him to decide. I liked pretty dresses but I also liked the breakfast treats after the marketing. So I had the best of both worlds.

Small as the market was, we could get everything there. Buah keluak, the quintessential Peranakan delicacy are poisonous nuts that had been buried in ash and lime to remove some, but not all of its toxicity. Grandmother made mother scrub and soak them for three days. Ah Lian, our Hokkien speaking help often cursed and swore as she had to delicately break the nuts at the lips. It was a difficult job to ensure the shells were not broken and her fingers not chopped off. The black meat of the buah keluak together with minced pork and seasoning were stuffed back through the narrow openings and cooked in a spiced broth made with grandmother’s special rempah, a mixture of pounded shallots, lemon grass and fresh chilli, which was sautéed in oil under low heat until fragrant. Even webbings of fat or caul to encase strips of liver and pork for Hati babi, another labour intensive dish , could be ordered from her favourite butcher.

Grandmother’s marketing retinue were mother, Ah Lian and me, like four musketeers. Grandma always hailed a trishaw. She directed the trishaw puller to as close as he could to the main marketing arena, to make the most of money paid for that short journey.

Along the way we passed chicken coops stuffed with their feathered victims, squealing pigs in their elongated baskets, and cart loads of spiky durians and other odoriferous fruits.

We tumbled out of the trishaw with our handled baskets. As I was a ‘budak lagi’, still a child, I was not allowed to make any purchasing decision. I was there to observe and learn. I trotted behind grandmother, as she continued to pile her purchases into my brimming basket. For an octogenarian, she moved with an uncustomary swiftness amongst the stalls. I was fully aware of her warning to remain within an arm’s length of her baju panjang, her ‘going out’ outfit made up of a sheath like dress, and sarong, otherwise I could well be kidnapped and made to work as a child slave. Mother and Ah Lian were ignored, except to fill their baskets with purchases and instructions, “Kangkong fry sambal belachan. Ayam cook curry. Don’t forget buy curry rempah at Pak Chick’s stall.”

I spotted mother and Ah Lian exchanging glances with a smirk and rolling eyes which flashed, “The same same same, always order people around, only.”

I had a morbid fascination with the seafood stalls which were an inevitable stop. Grandfather must have his piece of ikan goreng, fried fish. We could never predict what would be on offer on marketing day. The fishmongers knew that squeamishness was not an Asian trait, and freshness was their key to a sale.

Ghastly though the fish looked, I could not help but be fascinated by the row of fish heads fronting the slimy tables exactly at my eye level. Slashed clean, the gills continued to flap in unison even though separated from their bodies. I later learnt in school that the fish could not be alive as the movements were related to residual electric impulses that were sent earlier through the brain. Wide open jaws exposing tiny rows of jagged teeth and their glistening beady eyes looked accusingly at me.

The fishmongers fulfilled Grandmother’s criteria of purchasing the freshest seafood available. One of the main purchases was fish head for her fish head assam pedas, sour and spicy tamarind curry. Only the fish head of the ikan kurau or threadfin would do. She taught me how to identify a fresh head. If none were available my grandmother made a beeline for the fish ball maker. He had a stack of fish heads that were not fleshy enough for the flesh to be scraped out. Though not threadfin heads, they served to make a savoury stock for vermicelli fish soup with bittergourd.

My grandmother also had a particularly tasty recipe for fish heads. She cleaned the fish heads of scales, rubbed with salt and rinsed them clean. She sautéd julienned sticks of ginger and garlic in a few tablespoons of oil or lard till lightly golden brown, added a tablespoon of fermented soy beans to the ginger and garlic laced oil and sautéed the fish heads over high heat. The platter of fish heads which cost her barely anything was relished by my grandfather. This dish would satisfy the criteria of any slow food movement, had to be savoured slowly and with care. Picking the bones and hard cartilage for the remnant flesh was perilous. I recalled incidents where bits of bone and scales were accidentally ingested, making their presence felt in the diners’ gullets. Various remedies were immediately offered, the most common of which was to swallow a ball of compact rice. The folk logic behind this remedy was that the bone would hitch a ride on this fast moving ball, and glide harmlessly through the digestive system. It is debatable whether there is any scientific basis behind this theory but I cannot remember any family or visitor deaths from swallowing fish bones, despite the copious numbers of bony fish that had been consumed at our dinner table.

Grandmother gave me strict instructions to “jaga” or observe. I stood guard right close to the fishmonger as he gutted, guillotined, scraped and sliced. Like all suspicious housewives, grandmother feared that driving a hard bargain would result in the ensuing slimy package containing fewer pieces of fillet than what was paid for. I was to be her eyes, even when the flying scales flew in all directions and landed on my eyelashes.

Marketing was always organised when it came to Grandmother. There was no straying from the route which was directly connected to all her selected vendors. They humoured her as she questioned the quality of their goods, knowing that it was only for the sake of getting to an agreeable price. When the bargaining got too intense, they would say “Bibi, for you, Ok lah! You don’t want me to close shop, right?” and her stock reply was, “What close shop? You big towkay, I saw yesterday your new wife got berlian ring big big, diamond so kilat, shining that my eyes pain!“ And, depending on how close this was to the truth, there would be an exchange of money for goods, like two conspirators in a secret deal, or hearty denying, as his primary wife lurked in the background, wielding a chopper.

After the main purchases were made, grandmother would indicate that I could tag along with her to the delicious cooked food section of the wet market, leaving her two deputies to complete the mundane and standard buys with clear instructions to “buy from Pak Chick, his is always cheaper, then wait there.”

Mother took this opportunity to defy grandmother. She bought onions not shallots, telling Ah Lian onions were faster to peel. She preferred ikan bilis, dried anchovies to udang kering, dried prawns as they were healthier No, not from Pak Chik. Ah Lian was happy to conspire with mother against grandmother who had often bullied her into pounding bowls of peanuts into a paste for her rojak gravy, and cubing packets of pork fat to be fried into delicious lard crackers.

Mother and Ah Lian located our table and sat there, as a show of defiance. Mother ordered wanton noodles for Ah Lian and herself, ignoring grandmother that they had to be getting home. Mother smiled sweetly all the time and this made grandmother furious. Her weapon worked, and she even applied red lipstick right after she finished the last slurp, sending grandmother into a silent rage.

Like all Chinese matriarchs, my grandmother was not given to demonstrations of affection but I basked in her love as she lifted the bobbing white orbs of fish balls still steaming hot from the clear soup into a saucer. “Cannot let my chuchu choke, grandmother will cut small small for you,” as she fractioned the bouncy fish balls into tiny squares and speared them on a toothpick. “What does my Chwee Chwee like to eat? Chwee kueh ah?” as she chortled gleefully at her own private joke. Chwee kueh, literally translated as “water cakes” were steamed rice puddings spiked with a salty topping of preserved radish fried in shallot oil and the one snack that I disliked for their blandness.

Grandmother was illiterate, however she displayed her amazing intelligence and street wit playing puns with my Chinese name which means real water, and the unappreciated water cakes snack.

Grandmother revealed, “You know, Chwee Chwee, actually your real name was Kim Chwee. Aunty from No. 37 was good in fortune telling, when we gave her angpows. She told me that you were born in the month of the metal element. So having a “Kim” or gold in your name would not be good fortune, gold and metal, bo gum, cannot agree. To counteract this, there should always be water running in me, and nothing but the genuine stuff in my name could keep me in good balance.” So thus I became “Chin Chwee, genuine water.”

“No, lah, Mama joke joke only, here is the ban chang kueh for ‘my Chwee Chwee’, as she fondly stroked my cheek while I relished the pillowy triangles of sweet dough stuffed with roughly crushed peanuts and sugar crystals.

Grandmother’s teasing play on water was a side of her that was only revealed to me. To everyone else, she was the epitome of the stern, no nonsense, my word is law, maternal head of the household.

Tough as grandmother was, age eventually caught up with her, and a near fainting spell which brought her precariously close to tipping into the monsoon drain curtailed her marketing trips. As this coincided with the time I started formal schooling, my carrying the purchases duties were limited to Saturday morning forays with my mother. As second in command in the purchasing department, Mother had always deferred to her mother-in-law on the selection of greens down to the cut of pork. What a change in choice of purchases and in styles it was, when Mother was full fledged in charge. It was a ‘now I buy what I like, where I like’ against grandmother’s regulars. I was never sure whether it was just ‘a revenge’ against her mother-in-law or that she believed grandmother’s regulars were not as truthful as believed.

When mother took over the responsibilities of the daily marketing, I was not given those tender fish balls treats. She thought of marketing as a necessary evil. Armed with instructions mother had a mission to fulfil. But then, grandmother was not there to spy on her. Mother refused to patronise the ‘regulars’ because they would not allow her to prod and poke, while they insisted that Bibi had always trusted them. Mother went from stall to stall, making mental calculations on size versus price, and we bounced willy-nilly from fish to fowl, meat to marinade.

“Hey sister, don’t anyhow poke my prawn, want to buy or not?” or “You bend lady finger for what, I tell you fresh and young, you don’t believe. Break you buy.” “You say the fish not fresh, don’t buy lah! The gills so red you still say loco. You want really fresh, you go sea and catch.”

My mother answered each insult with narrowed eyes and offered a ridiculous price, bringing out the worst in the market folk, as they turned away to serve other customers. Dizzy from all the shouting and twists and turns, I feigned illness and refused to get out of bed on Saturdays, willing to forgo breakfast, which was not the regular feature which I had mother anyway

I watched the silent fray between the two strong-headed women. Sweet as grandmother was to me, she was the opposite with mother. She often took me in her confidence telling me how my Father defied her and insisted on marrying the ‘dark, skinny woman who was the daughter of the second wife who ran away from her gambling husband because he tried to sell their infant son, instead of agreeing to the union with the fair daughter of grandmother’s best friend.’

“Your mother when she came into this house did not even know how to pound sambal belachan” “But grandmother”, I retorted, “without Mummy, you would not have me, you also don’t like me, ah?”

“No, no, Mama not like that. Mama loves my Chwee Chwee Chuchu.”

“Grandmother, do you hate mother so much for marrying daddy? Is that why you always say she is wrong? Do you also hate daddy for going against your wishes?”

Grandmother was silent. I do not think that my childish reasoning changed her views over night, but they had an impact as I saw that she did not chide mother as often.

“Yes, Mama, I will make our “own” meatballs, as I turned to Alice, and said.” Don’t buy here, lah, tomorrow, we go to Pek Kio Market.”