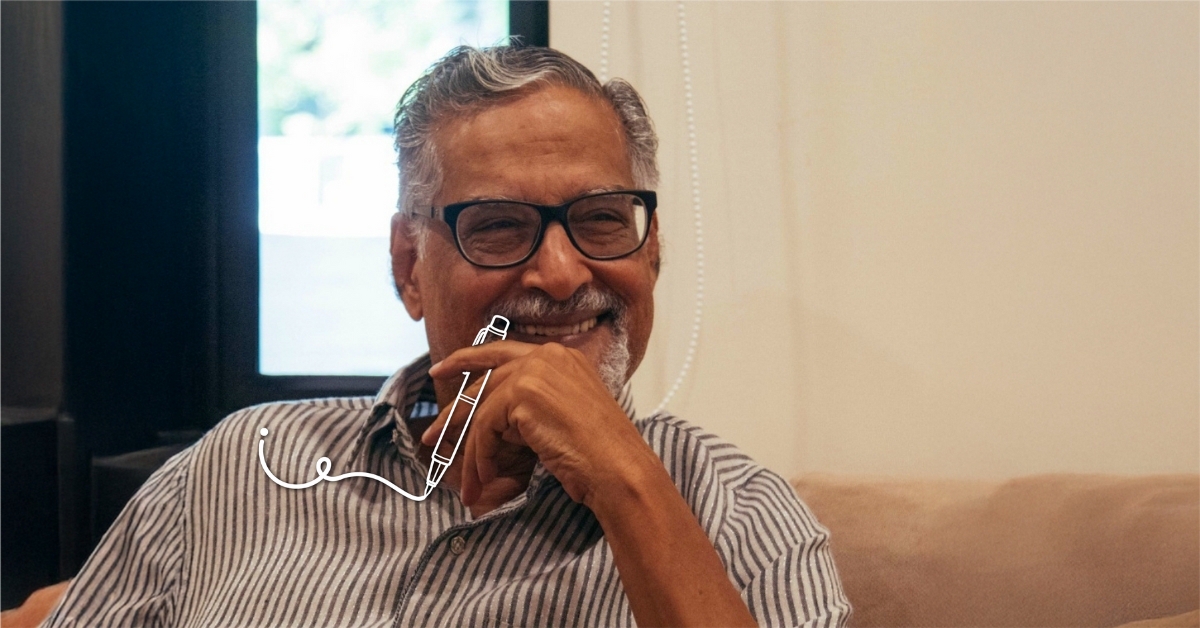

PN Balji is a veteran journalist with over four decades of experience in the media industry.

Renowned for his bold editorial leadership and commitment to journalistic integrity, he has held key positions at major publications such as The New Paper and Today, where he served as editor.

Balji is also the author of Reluctant Editor: The Singapore Media as Seen Through the Eyes of a Veteran Newspaper Journalist, a candid memoir that offers a rare insider’s view of Singapore’s media landscape and the complex relationship between the press and the state.

Through both his editorial work and writing, Balji has remained a prominent voice advocating for responsible journalism and thoughtful discourse in an evolving media environment.

Vintage Radio catches up with PN Balji as he reflects on his career.

Advertisement

PN Balji's growing up years and early influences

PN Balji was born in Kerala, India, and moved to Singapore when he was just one year old. He was raised in a large family with five sisters and one younger brother, PN Sivaji, who would go on to become a prominent national football coach in Singapore.

Growing up in Singapore’s naval base (in modern-day Sembawang), Balji found his childhood to be quite difficult, largely because he was the first son after five daughters.

For example, he alone wasn’t allowed to go outside and play.

She [Balji's mother] was very, very protective, and that, in the early stages of my life, affected me — you know, it made me a very reserved, maybe even reticent child. I hardly spoke to anyone,

he says.

Funnily enough his younger brother was given a much easier time, as his mother took it easier after her first boy.

Balji also recalls that his father, a Malayalam poet and stage actor, would wake up early every morning to read the newspaper. A young Balji soon followed suit.

By the age of 10 or 11, we began reading newspapers together,

he reminisces.

He didn't intend for me to follow in his footsteps or push me toward journalism. It wasn’t something he explicitly encouraged, but I think he influenced me through his example,

Balji says.

"It was because of him that I joined journalism."

However, Balji adds that his decision to pursue journalism was not solely due to his father. With his brother still in secondary school and his father retiring, he realised that university was not an option. As a result, journalism became the next best choice.

Discovering writing and career beginnings

Balji’s first job was as a relief teacher at Sembawang Primary School, though he quickly found another job in 1970 at what was then the Straits Times Press (STP), now known as Singapore Press Holdings Ltd (SPH).

It was a career path that starkly contrasted his shy and quiet nature. As he puts it, “Oh, journalism — you cannot afford to be reserved,” he shares.

Early in his journalistic career, Balji reported on crime at New Nation, a discontinued local English-language newspaper, a role with unpredictable hours that often stretched late into the night. Despite the demanding schedule, he thoroughly enjoyed the work.

However, he faced his share of challenges in journalism. On one occasion, he was arrested by the Corrupt Practices Investigation Bureau (CPIB) while making payments to ambulance personnel in exchange for information.

This started after a competitor publication, the long-defunct Singapore Herald, started paying the paramedics involved for information, resulting in them not wanting to talk to Balji and his colleagues without getting payment as well. It was a moment that highlighted the complex ethical dilemmas journalists face in the field when sourcing for quotes.

Editorial challenges and government relations

Throughout his four-decade career in journalism, Balji faced numerous editorial challenges, particularly in navigating the complex landscape of government regulations, which he calls a “minefield”.

Once, Balji’s career came during a tense standoff with government authorities over The New Paper’s decision to publish a Chinese New Year message in 1981 from the then-Prime Minister which included a crucial newspoint where the Housing Development Board (HDB) waiting list would be cut significantly due to increased construction and a strategy to allocate a portion of new flats for those on the waiting list, despite not receiving official clearance.

Traditionally, during Chinese New Year, the Chinese publications would stop printing for two days. Hence, the Prime Minister would release his Chinese New Year message early to the Chinese publications to accommodate their timelines, usually with an embargo for the English newspapers to not to release the news early.

That year, the embargo instructions were not given out. Hence, with the knowledge of the breaking news, Balji made the decision to translate the message from Chinese newspapers, and run it as a front-page headline.

This triggered backlash from the then-Prime Minister’s press secretary, who called the editor out for practising “Western-style journalism”.

Amid the storm, his then-superior walked into his office, put an arm around his shoulder, and said, “Balji, don’t worry, we are taking care of it.” It was a quiet, but powerful gesture of support that only strengthened his convictions.

Also read:

Stroke Survivor Rediscovers Joy And Purpose Through Art Thanks To Fellow Senior

After a life-changing stroke left musician Prisca Liang unable to play or sing, she found healing and connection in art, proving it’s never too late to start anew.

Orchard Road Busker Dubbed “Singaporean Kenny G” Ponders Retirement As He Crosses 70

The Orchard Road busker – best known for playing tunes from Kenny G on his sheng, an ancient Chinese woodwind instrument – is considering retirement once his busking license lapses.

Challenging the OB Markers

Another significant moment in Balji’s career was when he decided to print the headline “Senior Minister, I’m a gay. What is your stand on this?” on an article describing then-Senior Minister Lee Kuan Yew’s answer to a question regarding the gay community on live radio in 1998.

Balji’s decision to proceed with the controversial headline – despite his colleagues’ warnings – led him to an important realisation.

I would say the most difficult aspect of my journalism career was to try and not second-guess the government. Because sometimes what you think the government might be against is something the government is not against, then you have done a great injustice to your leadership,

he shares.

You could say Balj’s career was marked by a commitment to testing what Singaporeans would later call OB (or Out of Bounds) markers – a fuzzy, ever-shifting set of topics or issues considered off-limits for public discussion, particularly in the media and political discourse.

The press laws are very clear. But beyond that, there are many things that can be done. And I, being also the rebel in me, I thought to myself, 'why don't we test the boundaries?'

he says.

Balji’s strongest conviction as a journalist was perhaps his commitment to report the truth, even in the absence of formal mechanisms like a Freedom of Information Act, and often working against the odds to obtain critical information.

I think a defining editor is somebody who will report the truth, somehow report the truth as much as possible,

Balji shares.

We have to be, first and foremost, a responsible media,

asserts Balji.

“If you just give one point of view,” he warns, “then the reader will go away with that point of view. But that point of view may not be the right point of view.”

Conflict of interest and personal reflections

During the radio interview, Balji candidly addresses a personal and professional dilemma during his time in journalism, when his brother, PN Sivaji, was appointed as the national football coach.

Aware of the potential conflict of interest, he chose to step back from soccer-related editorial decisions, delegating the responsibility to his second-in-command.

I did something which I have regretted for many years, and I still regret, and that was to tell the journalists go and whack him,

he says.

The critical coverage of Sivaji’s performance ultimately took an emotional toll on the newsman’s brother, and he ended up writing a letter of apology.

It revealed a side of Balji not often seen in the newsroom – one that was softer, more introspective, and driven by a love for music, romance and justice. In fact, the silver once considered becoming a lawyer – though he ultimately found another outlet to express his beliefs of justice and responsibility.

Future plans

At 75, Balji speaks about ageing with his characteristic sense of humour, joking about the government’s aim to keep people alive until 85.

My grandchildren keep me on my toes, which means I might live beyond 85,

he says with a laugh.

His days are far from idle; he begins each morning by checking his calendar for appointments and makes time to meet friends, often engaging in spirited conversations about Singapore’s issues.

Reflecting on the journey of growing older, Balji likens life to a “sweet and sour relationship, like sweet and sour fish” acknowledging both its blessings and its challenges with the same thoughtful honesty that defined his journalistic career.

This content was originally aired on Vintage Radio. To listen to the complete podcast, click here.