Credit: National Archives of Singapore

On 9 August 2025, Singapore will celebrate SG60, marking sixty years of our nation’s independence. It will be a joyous occasion celebrated with activities to engage every citizen in one way or another, whether in the heartland or in the city centre. Many places will be peppered with joy and gaiety. Sounds of laughter will fill the air.nbsp;

The most awaited event would be the National Day Parade (NDP) to be held at the Padang, where the first birthday celebration of the country was held in 1966, on the field facing the former City Council and City Hall.

I was 14 when Singapore gained independence, and 15 when we had our first NDP.

That first parade was memorable – it played on our heart-strings. After years of turbulence, and being governed by others, we were finally free. My fellow Merdeka Generation and the Pioneer Generation were witnesses to history in the making back then.

I remembered how our kampong neighbours organized a lorry for us to go down to the Padang. It was a goods vehicle, so it had no passenger seats at the back. My ingenious neighbours simply roped a series of wooden planks across the back of the lorry and we sat on them. There was no back support.

Advertisement

We hung on for dear life all the way to town. Every time the lorry made a turn, we were swung from side to side. But we laughed and sang as we were happy to go to our first National Day Parade.

I covered this event in greater detail and many others in my two non-fiction books on my life in Kampong Potong Pasir. The books spanned twenty years of our country’s development. I wanted young Singaporeans to know how far Singapore had come.

(To my delight, the first book Kampong Spirit Gotong Royong/Life in Potong Pasir won the Singapore Literature Prize in 2014 and put me on the literary map here.)

The flags of Singapore

At every modern NDP, the helicopter hoisting our giant national flag gently fluttering against the blue sky passing the parade grounds will trigger off deep-seated emotions in our population – especially so for my generation. The sight of that flag would make our hearts swell with pride anew and bring tears to our eyes.

This is because we had lived through changes of governance and national flags. Besides the ancient Straits Settlements and Japanese flags, our generation had to bow to the British Colonial and Malaysian flags before we could finally venerate our own. For once, we could stand proud.

In 1959, when we gained self-rule, Deputy Prime Minister and Founding Chairman of the PAP, Dr Toh Chin Chye, and his task force committee designed our own state flag. The meaning and symbols of the colours, crescent and five stars are now familiar to every Singaporean.

I feel that the symbol of this flag is particularly significant for those of us who had served under the colonial yoke. It was folded away for the years when we were part of Malaysia.

National anthem

Like the state flag, Dr Toh Chin Chye also had a hand in editing encik Zubir Said’s composition, Majulah Singapura, to make it shorter and to tweak its melody so that ordinary people found the tune and words easy to recall. It became our national anthem.

Although the Merdeka Generation were not subjected to the Japanese national anthem during the war, we had to sing various others before we sang our own – God save the King when King George was on the throne, and God save the Queen when his daughter, Elizabeth II took over his mantle. We also sang Negara Ku when we became Malaysians.

Majulah Singapura was first sung in public in 1959 when Singapore gained self-rule and to commemorate the re-opening of the renovated Victoria Museum.

Like watching our own nation’s flag unfurl for the first time, that event at the Padang in 1959 was tremendously emotional – I was just an eight-year-old singing our own national anthem back then. I recounted this tremendous moment in my book.

From that moment, we became united as one people, with a united purpose and cause, though we still hadn’t used the term Singaporean generally.

1965 was a traumatic year

A caesarean birth is one where the baby is not born by natural means but through surgery. It can be said that the baby is forcibly removed from its mother’s womb.

That was how it felt for us who were ousted out of Malaysia on that fateful day on 9 August 1965.

Even before this had happened, Singapore was beset with problems by Konfrontasi (a period of armed conflict between Malaysia and Indonesia, with Singapore involved as part of Malaysia), which led to several bombings, including the tragic one at MacDonald’s House.

Though I grew up in the kampong without electricity and running water, the newly minted PAP fulfilled their campaign promises and gave our village a new road and electricity.

So, we could watch the RTS (Radio Television Singapura) telecast on black and white on our locally-produced Setron TV when the announcement was made about our split with Malaysia. The founding Prime Minister Mr Lee Kwan Yew was captured at an emotional ebb.

Singapore was forcibly thrust into independence and even PM Lee was unsure if we were ready. Many people were affected at ground level. People had to choose to be Singaporeans or move to Malaysia to remain Malaysians. Families were being torn apart. We lost family and friends during the exodus.

Credit: Penguin Random House

One of my best friends and neighbour, Fatima (not her real name) and her family moved upstate. I was devastated and have been looking for her since. I fictionalise this angst in two of my stories in my new collection of short stories, Merdeka Generation Groovers and Other Stories, due to be released on 5 August.

It was a challenging task to locate Fatima as she did not leave a forwarding address in Kuala Lumpur. She couldn’t read so we couldn’t communicate by letters. Back then, we were also all too poor to own telephones.

Education for the masses

For many of us of the older generation, especially those of us who were brought up in impoverished villages, Mr Lee will always remain the charismatic and wise leader who took us out of poverty.

He created jobs for us through rapid industrialisation and he made education affordable and a priority for the masses.

Education is an avenue out of poverty.

He had the foresight to say,

He also set up Lembaga, a now-defunct adult education centre for adults who had never gone to school or never made it to secondary schools.

Through such efforts, women also started to enter the workforce. Girls like myself in these villages had little or no education because our family had no money to send us to school.

Because I ranted and raved to go to school, my mother eventually found a solution. She made Nasi Lemak and I had to go round the villages to sell the packets before I could go to school. I was only aged seven then.

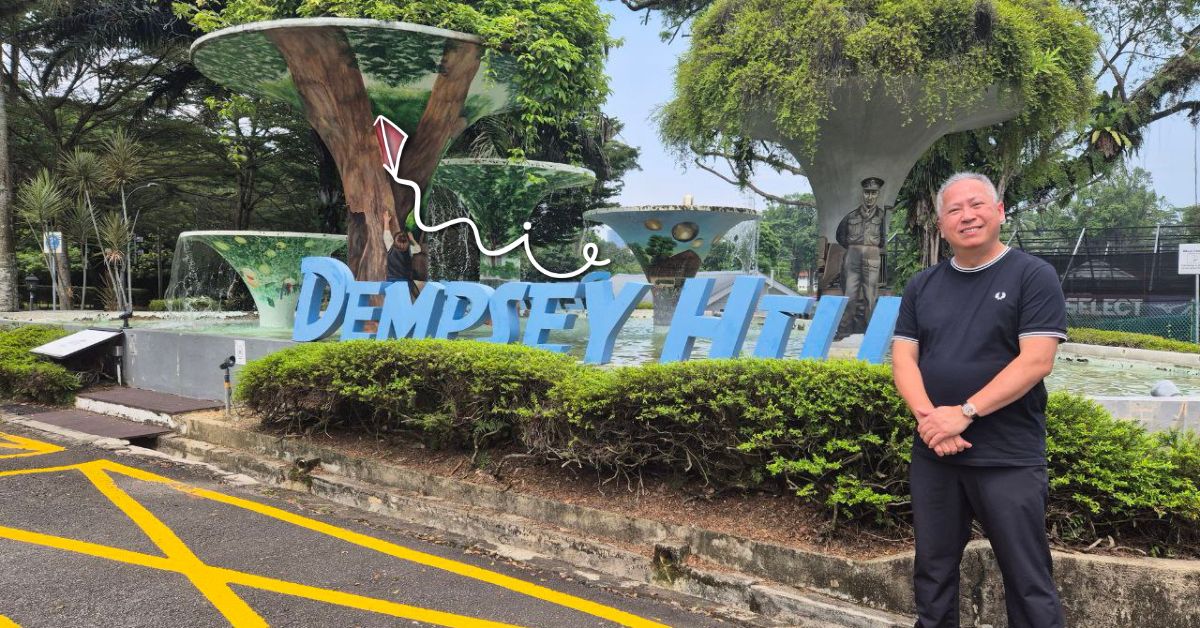

Credit: Josephine Chia

I was lucky that my elder brothers had also started working and could help finance my education. Some of my dearest friends in my kampong never got the chance to be educated.

People mistook them for being stupid because they could not speak English. I wanted to show that ignorance is different from stupidity. They may be intelligent but they didn’t have the opportunity of education. That’s one of the reasons I wrote my kampong books – it’s for them.

Modern successful women

Successful women during that period tended to be from middle- and upper-class families. Fatima would be proud to know that one woman from her community, Che’ Khatijah Nissa Siraj, co-founded the Young Muslim Women’s Association and the Muslim Women’s Welfare Council to create better protection for Malay women. She was an activist and had been inducted into the Singapore Hall of Fame.

The Peranakans were a touch more fortunate. Dr Lim Boon Keng and his colleague Sir Song Ong Siang felt that girls needed to be educated too, so in 1899, they had opened the Singapore Chinese Girls School on Hill Street. Only seven girls attended back then. They were from privileged families.

It’s only after Mr Lee Kuan Yew focused on education for everyone did women from kampongs and HDB heartlands emerge as female pioneers in numerous fields.

This year’s NDP fly-past will include a female fighter pilot, 27-year-old Captain Rachel Wong. In 2015, 37-year-old Major Lee Yi Mee set the precedence to be included in the fly-past.

Such achievement for a woman was unheard of in pre-independent days, even though the Women’s Charter was created in 1961. Of course, there were achievers in other fields as well.

We may take such things as for granted these days, but it has taken years for women here to establish ourselves as professionals in this society.

Independence exacted a price

It was no plain sailing for our country immediately after we became independent. The ground beneath our feet shifted.

Most of the people living in kampong squatters had inherited post-war conditions, lack of proper sanitation and housing, as well as lack of food and jobs. This was exacerbated when the British started pulling out 15,000 people, comprising troops, staff, and businesses.

17,000 of our local men and women who had been employed by them suddenly found themselves without work and income. The ruling party, PAP, worked diligently to create jobs and opportunities for the people. It was through the government’s efforts that we did not succumb to internal chaos, depression, nor destruction.

Bonding through hardship

Because the Pioneer and Merdeka Generation elders had experienced the hardships of the development years of Singapore, there is a strong connection with the nation.

We came to call ourselves Singaporeans. We grew and developed with the nation, and people found their niches and made good their lives. Our bond was forged by a metaphorical fire that bound us steadfastly to this country.

Unfortunately, our children and grandchildren didn’t see or experience our hunger and sufferings. They were born into a Singapore that is now a first world country, not the third world one that we knew. They were born into robust housing that were not subjected to the vagaries of the weather. They did not have to share their bathrooms and toilets with their neighbours.

Most parents of this current generation still work hard to send their children to school, and some even send them to schools and universities abroad. This has resulted in a new breed of young people who are emotionally detached from the welfare and challenges of modern Singapore.

Invariably, this can lead these young people to not feel any loyalty towards Singapore. The consequent problem that results from this is that their parents are left bereft if their partner or spouse should leave them or die, whilst their children are far from home.

The latter are subjects I also tackled in my new collection of fictional short stories, Merdeka Generation Groovers and Other Stories. (Yes, it does take a whole book to talk about such things).

SG60 and beyond

Thus, we have to find some way to engage with our young people before they go abroad. We have to instill in them a conviction that Singapore is indeed their home. We have to convince them that we are all truly Singaporeans.

Come 9 August 2025, we can all stand proud to sing Majulah Singapura with gusto, and to enjoy the fireworks display in awe. Our journey into nationhood has not been easy.

The Merdeka Generation and Pioneer Generation will still be around to tell their story this SG60. They are the living historians of our turbulent past. Engage with them to realize just how lucky we are today to live in a prosperous, safe, and beautiful Singapore.