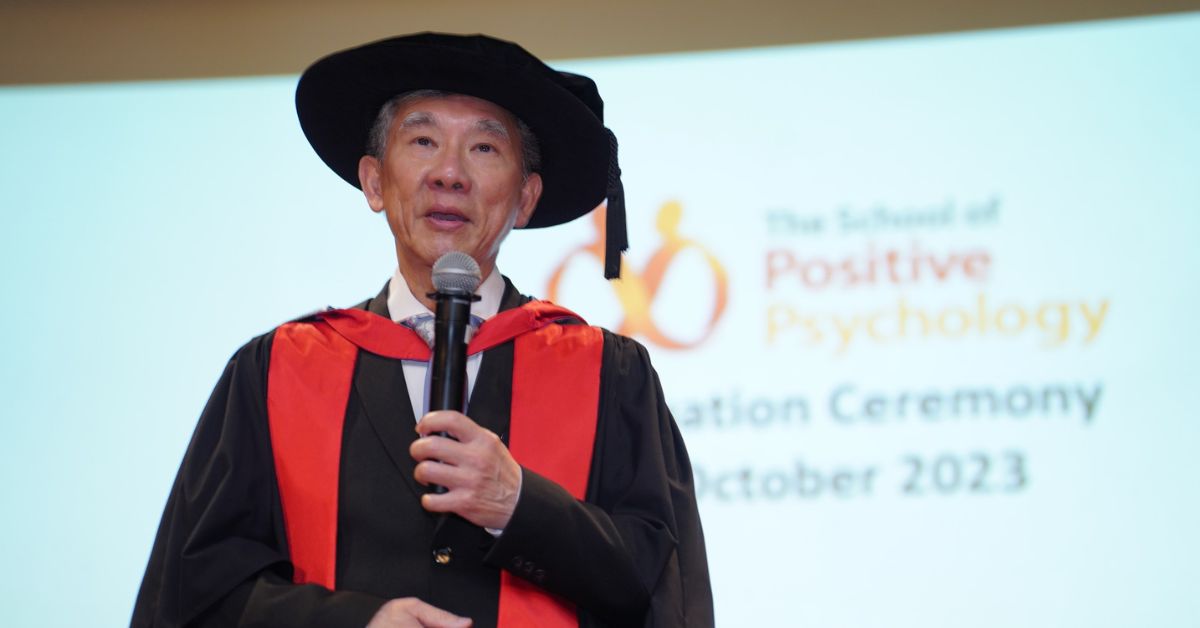

Dr Titus Foo, 71, head of research and founding board member at The School of Positive Psychology (TSPP), feels that Singaporeans are always in a rush.

“In Singapore, we are rushing all the time. We give way to other people by rushing ahead. You get in a bus, and so often, it’s jerky like a roller-coaster. Not because the bus itself is old, or the driver’s skills are bad, but because he’s always rushing,” says Titus.

“We can afford to let ourselves take a break; there’s no engine that can keep going 24/7. If you keep pushing it, you will break down,” he adds.

It is a sentiment characteristic of positive psychology, an emerging branch of the field that deals exclusively with, well, the positive – feeling positive emotions, cultivating positive character traits (or strengths) and creating positive institutions. It is Titus’ current area of focus after decades in the realm of psychotherapy.

“Positive psychology distinguishes therapy from wellbeing. If psychotherapy is bringing you from negative 10 to zero, positive psychology is about boosting your wellbeing. We aim to take you from zero to 10; from happy, to very happy,” he says.

Advertisement

Titus Foo: The Go-Getter

It’s no mumbo jumbo, see, as Titus himself has lived most of his life in the fast lane.

In the two years between graduating from St Joseph’s Institution to his national service back in 1969 when he was 16, the second youngest of seven siblings worked three jobs: Sales at Metro Department Store, which he enjoyed greatly, then back-end operation roles at a hotel and warehouse, which he didn’t find quite so fun.

Things picked back up when Titus was called up for the army – so much so that he decided to stay in the organisation for the better part of three decades.

Along the way, he squeezed out some time from his duties to get educated, picking up a bachelor’s degree in psychology — with a second major in political science as well as a minor in philosophy — in Canada, then a master’s degree in psychology in the United States, within the space of two short years to maximise his time in North America (possible thanks to the “extreme flexibility” offered by overseas universities in planning a jam-packed schedule with lots of classes during summer break).

Though brief, the studies gave the man the qualifications he’d needed to switch tack and pursue a growing passion for psychotherapy and psychology a couple of decades later after leaving the armed forces at age 42.

Just as before, Titus’ next couple of decades passed by like a whirlwind – immediately after the SAF, he lectured at Nanyang Polytechnic and James Cook University; worked at a psychiatric clinic in Mount Elizabeth; got a PhD in psychology; moved to New Zealand; got a post-graduate degree in cognitive behavioural therapy; moved back from New Zealand; and joined up with TSPP, all the while working with people from all walks of life.

Why reflect?

It was during this period when Titus started realising on the importance of mental health and being more reflective as you age.

When I was working in a psychiatric ward (at Mount Elizabeth), we were visited by people as young as five, and as old as 95. We had patients who were middle income, all the way to royal families. What that tells me is – everyone can have issues with their mental health,

he explains.

But for silvers who might’ve “never taken the time to consider their mental well-being”, reaching that point of net zero is difficult without proper introspection or the help of a professional.

Without taking a pause to reflect, most people go through their lives not knowing if those issues at the back of their mind are something serious. Oftentimes, they only find out because their mental health starts to affect their physical wellbeing,

he adds.

Ease back on productivity

Another oft-observed side effect of a Singaporean upbringing is a competitive mindset that turns into an insatiable hunger for productivity. Titus was the same when he was younger (as seen in his hunger for paper qualifications in his 20s) but has mellowed since then.

We're so much into productivity that our first thought at the end of anything is, 'Okay, what’s next?' You've retired? Okay, what should I do next? What can I do next? How can I contribute?

he says.

We should really start with simply 'Well done',

offers Titus.

"And then – nothing. Literally, stop and smell the roses, appreciate your achievements, be grateful for what you have. That’s all."

In that vein, retirement, therefore, should begin with an introspective look at what you really want to do in the next chapter of your life.

Take a really deep look at yourself and think. If that's what you really want to do, go for it!

Titus avers.

"Everyone should be true to themselves. If you want to go for a mid-career change in your 50s and 60s, don’t stop yourself because of face or reputation."

After all, Titus took on his new head of research role just last year, at the age of 70, wanting to contribute to the nascent field of positive psychology research.

Regardless of what happens, all that’s left in 50 years is just a memory. And when that’s gone, it’ll be gone forever,

he adds.