A vignette by Jasmine Adams

As a child, I was nicknamed little Miss Butterfingers. Even though I was the sole owner of a family of imported dolls, I never had the pleasure of playing hostess at their tea parties.

Entrusting me with the responsibility of pouring the tea would inevitably result in miniature teapot cover flipping off or a misdirected spout resulting in a spreading stain on Barbie’s pinafore.

Given my propensity towards accidental slips, I was not deemed to be kitchen assistant material and banned from the exciting arena of smoke and smells presided over by the women folk in my family.

My earliest memory of food in its semi-original form brought memories of a high pitched yell. “Yau Siew” was a Hokkien vulgarity, and emanating from my sedate and ladylike grandmother, most surprising indeed! She accompanied that heart rendering curse with a frenetic waving of a feather duster in her attempts to thrash the cause of her unhappiness.

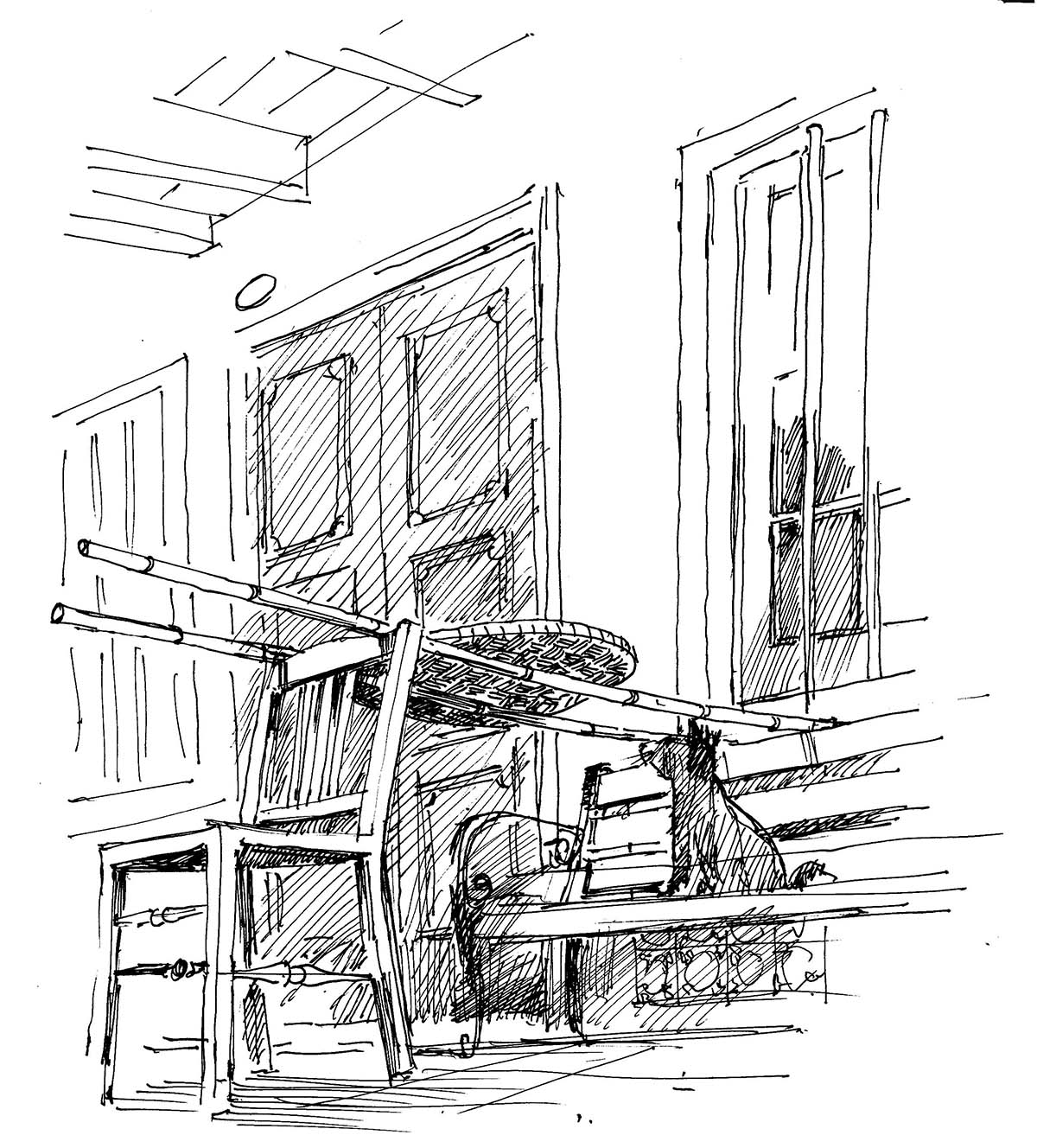

Preceding this outburst, there was a crashing sound of bamboo and metal and the swish of a furry tail belonging to an accursed feline who will, undoubtedly henceforth, be destined towards a difficult and foreshortened life.

Excited by the cacophony, I finished on the home square of the hop scotch game and rushed to the scene of the crime.

My untrained nose detected a pungent odour totally disproportionate to the dismal mess which confronted me. Mud cakes lay flattened into unmentionable shapes on the pock marked and dusty cement five foot way. The bamboo tray which was their most recent residence bore few marks of their existence having toppled down along with the supporting poles meant usually to hang laundry.

Advertisement

This unsteady contraption which rested on odd chairs worked well for drying less tempting products but my neighbour’s cat was undeterred by the challenge of this precarious perch when it came to belachan.

My absence from the hallowed walls of the kitchen was a primary cause in my lapse in understanding the direct connection between these disintegrating slabs to the most important condiment on every Peranakan’s dinner table.

My grandmother’s precious patties of belachan had become shapeless forms which would not have the opportunity to harden and mature into solid grey rocks. Our family recipe for belachan was “purist “and made from the freshest miniature shrimp known as grago.

These tiny shrimps were deeply ingrained in our historical and cultural beginnings. Not just an insulting word for Eurasians who incorporated them into their daily diet, they were also associated with Portuguese colonial masters. Another but not often used name for belachan was Melaka cheese.

In her book “the Golden Chersonese” Isabella bird explained how this association between tangentially disparate but acquired tastes could be made –

“…The boatmen prepared an elaborate curry for themselves, with salt fish for its basis, and for its tastiest condiment blachany – a Malay preparation much relished by European lovers of durian and decomposed cheese. It is made by trampling a mass of putrefying prawns and shrimps into a paste with bare feet …”

Given that true blue Peranakans have paternal Chinese origins, the use of this ubiquitous condiment was a strong influence from their maternal Malay roots . A likely by-product of the remnants of a day’s catch left out too long in the baking sun which evolved into food, many South East Asian cuisines have their equivalents. The Thais have their kapi / kapee, the Filipinos, their alamang and the Indonesians their terasi, humble essentials which elevate simple repasts of rice and vegetables into memorable meals.

These days, making belachan from scratch in Singapore may be an insurmountable task. These miniature shrimps have become an unprofitable product to sell to the retail customer and are not available even in the most esoteric seafood market. Understandably, making belachan at home according to secret family recipes is now an extinct practice in our city state.

From start to finished product, there are many steps in the production of belachan. Fortunately for all of us, compressed bricks of ready prepared shrimp paste are easily available in any Asian supermarket. Those who prefer a more authentic and rustic taste can still venture into fishing villages in Malaysia as they are still made by fishermen’s wives. Seawater and fresh sunshine may make for less stringent hygienic production standards than the cottage industries which export far and wide but according to connoisseurs yield a taste sensation comparable to none.