The above quote was spoken by my child-character Amelia, who was talking about her Peranakan great-grandmother.

This issue about language is one that modern Peranakans have to face, with our children marrying non-Peranakans and the old patois disappearing as the grandchildren are unable to speak it.

Thus, communication these days has to be in English. Other issues that are affecting us include the finer aspects of our culture diminishing as customs and heritage are no longer being practised or upheld.

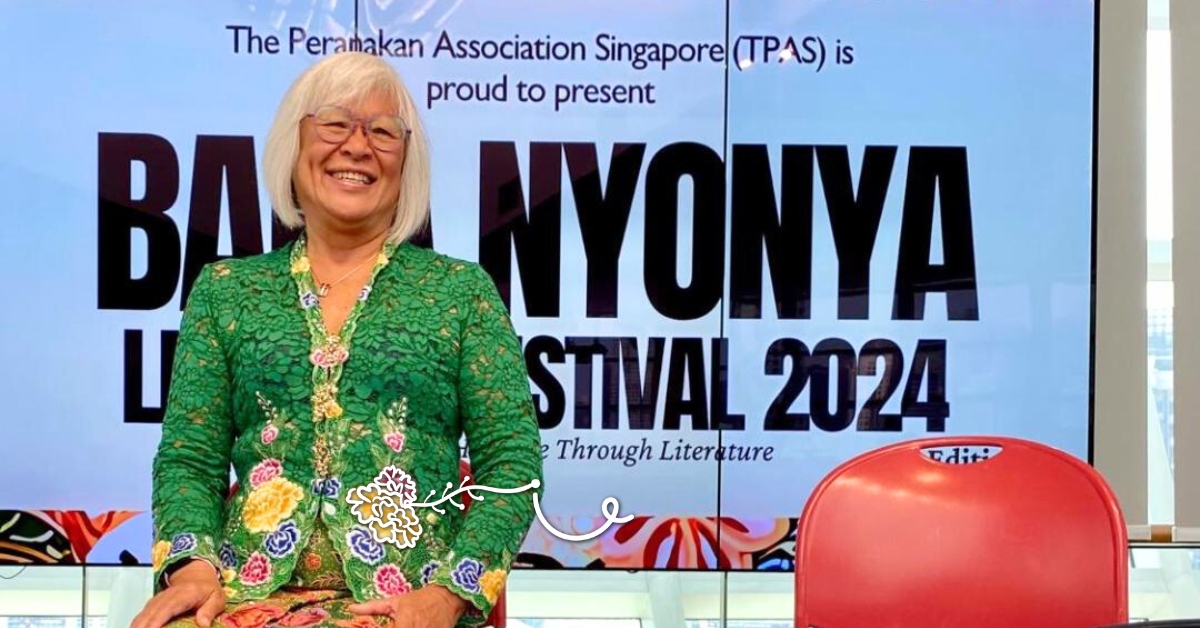

People like myself, who are proud to be Peranakans, are actively spending our last years making our culture known, passing on our legacy to those who wish to carry the torch forward.

Pride in our heritage comes from loving the uniqueness of our fusion with the Hokkien (also Teochew) migrants from China who may or may not have mingled with local Malay, Indonesian and even Dutch and Portuguese ancestors – leading to the creation of our own richness of culture, customs and cuisine.

Peranakan may not be considered a ‘race’ but those of us who are Peranakans grew up with a special ethos and way of life that is not like any other Chinese community. We are most certainly chelop or a hybrid, either in blood or practice, taking the best from other cultures and incorporating them into our own.

In many ways, the female is the bastion for passing on heritage.

Particularly in the old days, women’s role was clear-cut, designated to be householders and nurturers of their children. Women were bred to make babies and to satisfy their husbands’ sexual appetite.

In modern feministic terms, they were no more than breeding cows and objects of men’s pleasure. It was unlikely that a woman could express her feelings, thoughts, desires and dreams.

Without any education, women during that period had little choice but to live within societal norms; unless they happen to inherit their father’s or husband’s fortunes and thus have some clout to resist conventions.

For the women assigned to a lifetime of making babies to ensure their husband’s posterity, there was no medicinal form of contraceptive to prevent pregnancies. The desperate would indulge in folklore methods or home-manufactured ones like eating sour pineapples, pushing a vinegar-soaked rag up the birth canal, swallowing baby mice or cockroaches or jumping up and down to induce a miscarriage.

Women like my mother had a child every other year of their fertile years.

In this draconian milieu, for a woman to exist in some measure of contentment, the woman had to make herself excel in the home. It was more convenient for the men to relinquish the role of running and maintaining the household to the women to concentrate on their careers and businesses.

So, inadvertently, women developed a bastion of power in the home, thus establishing a matriarchal kind of supremacy in her domain.

Women honed their skills in feeding the family, providing beautiful clothes for men, women and children; curtains, sheets, altar cloths and accessories in the home in the days before mechanisation and modern sewing machines.

Most things had to be done by hand. It was the job of the woman to create. They set the standards of excellence in their homemaking and crafts.

A daughter is trained diligently to adopt her mother’s skills. A daughter-in-law is chosen on the basis of her proficiency in knowing how to tumbok belachan (pound sambal belachan), the excellence of her Ayam Buah Keluak dish, the fineness of her embroidery where stitches were controlled and delicate, her art of beading slippers in pleasing designs and colour.

A woman learnt to be deferential and how to always put her husband first and never to criticise him in front of others.

Less privileged Peranakan women learnt similar skills, sometimes to put food on the table, sometimes to attract the right man who would take her out of poverty.

The clever and wise wife learnt how to make herself indispensable. Fanning her husband’s ego is one thing, making him a success in society is another. The Matriarch was formidable in making the right connections to ensure her husband’s rise in society. His success was hers too, as she would gain status as the wife of a prominent man.

In the days when restaurants were not that prevalent, the Matriarch would organise dinner parties for her husband’s business associates and would personally get involved in the cooking to achieve her goal.

She didn’t cut corners – ingredients had to be fresh, slicing, pounding and frying swelled to an art form, taste could not be compromised. Care was given to details – the buah keluak had to be cleaned properly for five days to ensure that the poison was removed, the pork leg had to be marinated with salt to remove any odour.

Men in the past had to prove their virility by the number of children they had, and even by the number of women they could own. There was not a lot a wife could do to prevent the latter, especially as she aged.

But the astute Matriarch had to exalt her own importance and relevance so that she would always remain the number one wife, providing not only heirs but a cohesion of family support to the husband so that he would always make his way back to the original home.

It was a revolutionary move, catapulting women into a level playing field. Now women can be who they want to be – nurses, doctors, mathematicians, engineers, etc. Women no longer had to skulk around men’s heels.

With their improved standard of English, they entered the Civil Service, professional and legal careers to earn their own money, thus removing the bondage to a man.

Yet women like myself, being brought up in impoverished kampungs were still trying to catch up with privileged women. It was not until Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew decreed that girls of all societal levels must be educated did the movement towards female emancipation really began here.

My mother had to cook her nasi lemak and sell it to earn school fees before I could get to school. I was nearly eight before I learnt my English alphabet. I fell head-over-heels with the beauty, cadence and nuances of the English language, which became a life-long affair. It was inevitable that I eventually became a writer.

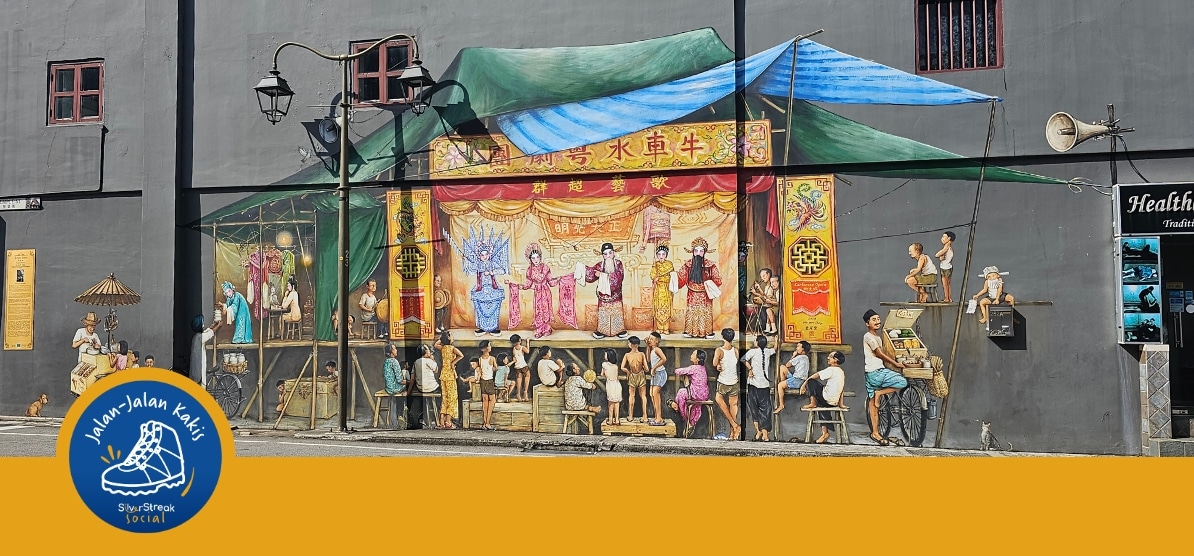

Socially and business-wise, the Peranakans form a tight community. Perhaps because we represent a smaller sub-section of the larger Chinese group, there was a need to bolster each other, to celebrate our own unique cultural identity.

For many years, Peranakans were caught in a crossfire of being neither truly Chinese nor Malay. The Malays called us OCBC (Orang China Bukan China) after the acronym of a local bank. Chinese But Not Chinese.

Our women dressed like the Malays. We used our fingers to eat our food, but we consume pork, which was anathema to the Malays.

To the Chinese, we were not Chinese as we did not speak mandarin or local dialects as we conversed in our own patois and our women wore the sarong kebaya. It could have degenerated into a Lose-Lose situation.

And yet, people respected our right to be ourselves.

Now, Peranakan restaurants are sprouting like dragon’s teeth. Though we shared the rendang, sayur lodeh and other dishes with the Malays and Indonesians, our brand has become our own.

I am proud of this and love to eat and cook our kind of food.

There is a certain je ne sais quoi about the spirit of the Peranakan that is delightful. Men and women make opportunities to congregate in our finery, parading like colourful peacocks.