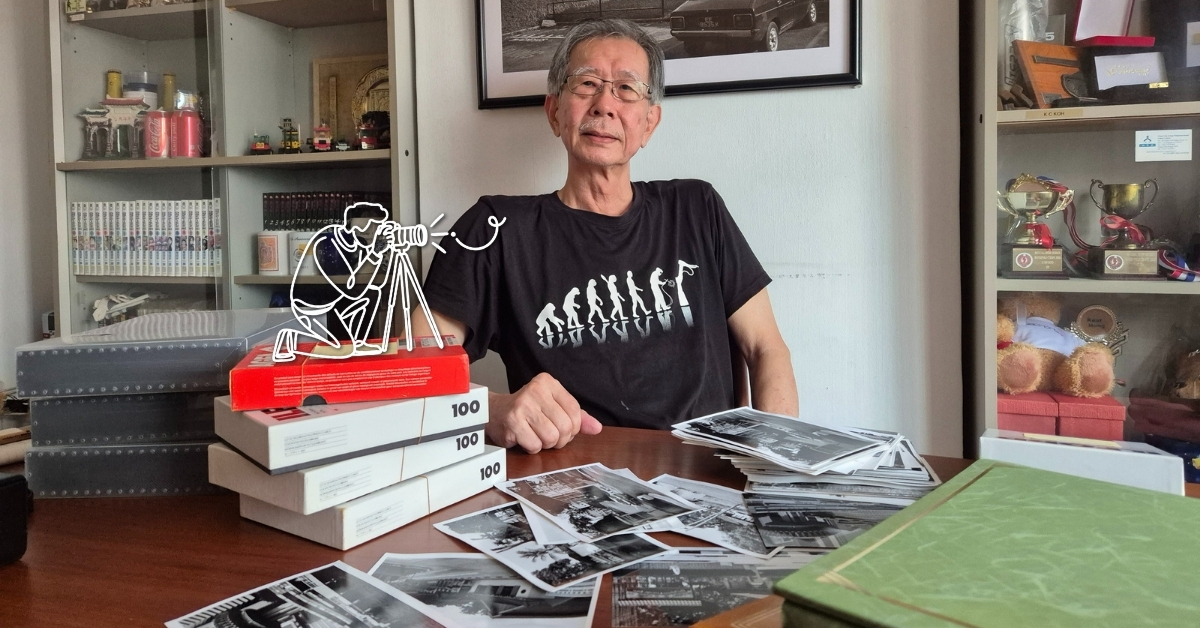

Hidden within a nondescript black cupboard in Koh Kim Chay’s HDB flat is possibly one of Singapore’s most extensive collections of archival photography and postcards – at least where it comes to pictures of long-forgotten buildings, disappearing places and vanished public housing estates.

The hobbyist photographer estimates that he has over 7,000 pictures in print — meticulously developed, labelled and arranged within glossy black folios — dating back some 40 years.

Anything digital can be corrupted, you see. If you have something valuable, you print it out,

he says.

"Then you can be sure it'll stick around to be passed on to the next generation."

To be clear, the 69-year-old isn’t averse to modern technology. He has even more photographs tucked away in hard drives — numbering in the tens of thousands — though they aren’t significant enough to make the cut for development and printing.

I'm just enjoying my hobby. Whatever scene I take the time to process has to be interesting to me – if not, I won’t bother.

Kim Chay says with a shrug,

Advertisement

Started hobbyist photography in the ’80s

The retired engineer has been a collector at heart since his childhood. He cut his teeth soaking stamps off discarded envelopes, which he collected from dustbins near Market Street where his parents ran a hawker stall.

He eventually joined the Singapore Stamp Club, which led him to a stamp fair where he found his enduring calling in the postcard scene. The larger format print, he felt, had “a strong archival quality to it”, both for its size relative to stamps and ease of processing.

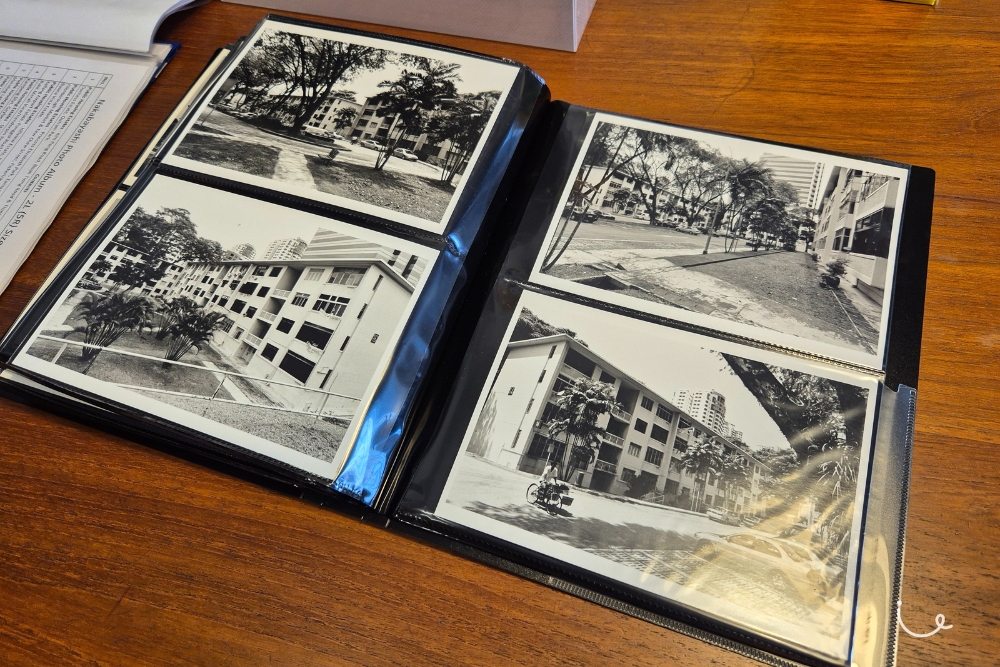

Though the majority of available postcards were “touristic sights” like the National Museum and Fullerton Hotel (formerly the General Post Office), Kim Chay preferred “offbeat sights” – “the places that no one pays attention to, but have always been there, sort of in the background”.

Naturally, postcards of these places weren’t always available – which was when the senior decided to start making his own records. Armed with a film camera and access to SAFRA’s dark room at Mount Faber, he began exploring Singapore’s neighbourhoods in 1986, documenting buildings and landmarks that he felt were underrepresented.

These include Princess Elizabeth Park, an early housing estate developed by the Singapore Improvement Trust (the predecessor to the Housing and Development Board); Forfar House, once Singapore’s tallest residential building at 14 storeys, leading to its Hokkien nickname of “chap si lau”; the Sungei Road ice factory; and the former National Library Building in Stamford Road.

The silver’s fastidious notetaking accompanying each of his photographs only adds to its historical value.

All collectors are minor historians. History is what makes the collecting so exciting.

He says,

Capturing vanishing Singapore

As time progressed, all of these buildings were torn down, renovated or otherwise repurposed. Kim Chay’s growing collection of disappearing places in black and white became all the more valuable.

In 2017, the senior published Singapore’s Vanished Public Housing Estates together with a fellow photographer, immortalising 27 of the country’s earlier flat developments before they were lost to memory forever.

He later donated over 7,000 photos and postcards from his collection to the National Library Board.

As of yet, the silver hasn’t made concrete succession plans for the remainder of his collection. Kim Chay might pass it on to his adult son, though he understands if the younger Koh doesn’t want to grow it any further.

He knows it has value, but he has his own life to think about. I just told him – if you want to get rid of it, don't sell it, just donate it to the National Archive,

he says.

In any case, money has never been an end for Kim Chay’s various collections.

It's never crossed my mind. I'm lucky that I'm not financially strapped and have a supportive wife,

he says.

"But most of us collectors think the same way – try not to think of the cost. Just enjoy the hobby."