When I met Tanya Pillay-Nair at a cultural walk a few years ago, little did I know that I would be privileged to uncover a nearly lost — but not forgotten —cuisine that has existed and evolved over 500 years.

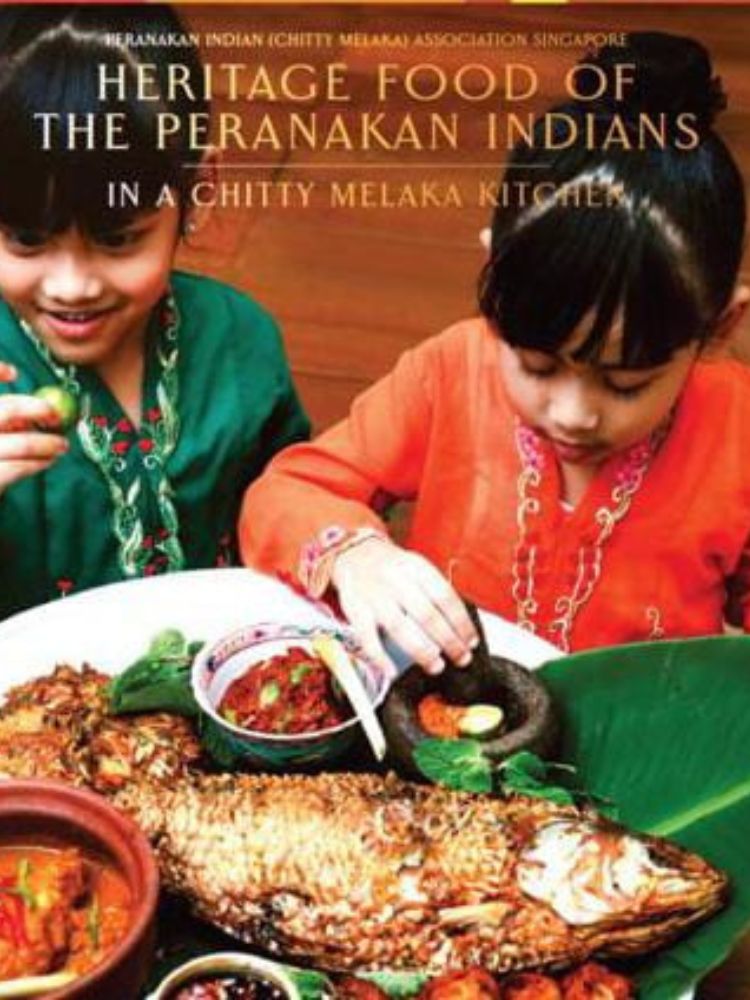

Tanya is an Indian Peranakan who is passionate about her roots and the coordinator of the Heritage Food of the Peranakan Indians (In a Chitty Melaka Kitchen) cookbook, a project of the Peranakan Indian Association of Singapore. I served as the co-editor of the book.

The term “Peranakan” has long been associated with its Chinese community.

However, the Peranakan Museum of Singapore, recently reopened on a more inclusive note, embracing their definition of “Peranakan” to refer to “locally born” descendants of mixed parentage; a result of the union of local womenfolk with foreign fathers from China, India, the Middle East and beyond.

Thus, Indian, Arab, and Jawi Peranakans have been given a presence side by side with Chinese Peranakans, with audio, visual, and material artifacts.

Advertisement

The Peranakan Indians or Chitty Melaka communities have been in existence for hundreds of years, tracing allegiance to Parameswara when Indian traders formed unions with local women during the Melaka Sultanate.

Over the years, due to encroachments under the rule of various colonizers of Malacca, including the Portuguese, Dutch, British, and Japanese, and Malaysian independence, the village which once had more than a thousand inhabitants, shrunk, and many Indian Peranakans migrated, many to other parts of Malaysia, Singapore and beyond.

The distinctive culture and cuisine of Indian Peranakans are derived from the adaptive adoption of ingredients and cooking methods from their South Indian homelands and the integration of local elements obtained through foraging, fishing, and farming.

Taste Markers

What are the markers of Indian Peranakan (Chitty Melaka) cuisine?

For one, strong and indelible influences from Indian forefathers has seen the inclusion of spiced salads and pickles, common staples such as rasam, a watery comforting broth, to be eaten as an appetite arouser or like a soup to moisten rice and bread, curries, and sweetmeats.

Though white rice is served for daily meals, celebratory meals include pilau, saffron rice studded with cashew nuts and raisins, which translated into nasi minyak for the Chetti Melaka, rice cooked in a type of oil, with ghee from cow’s milk being a must.

However, the true signature rice dish of the Indian Peranakans particularly for “parachu”, from the Tamil word “padaiyal” that means offering, is their outstanding “nasi lemak kukus”.

Nasi lemak is commonly known to locals simply as rice cooked with coconut milk.

“Kukus” means steamed in Malay, and the process of making this rice involves many steps, including pre-soaking the rice, double steaming, and subsequent immersion in freshly squeezed thick coconut milk, and even a drizzle of lime juice, which ensures that each grain of rice is fragrant, plump and glistening.

As with rice, many other dishes have become localised in Indian Peranakan cuisine.

Yogurt was not easily available, and as its fermented sour notes did not sit well with the locally born, who were brought up with always being wary of food that goes off (which very commonly happens in our hot and not too well-ventilated kitchens and dining areas), they replaced this ingredient with creamy coconut milk.

However, whole and dried spices travelled well and are still used liberally.

Adding another layer to these warm earthy spices, are aromatics such as lemongrass and pandan which infused their way into becoming mainstays of many recipes.

And even though many recipes will carry the same names as their Indian counterparts, the taste profiles are totally different and in fact, our chefs from India who played a big part during the recipe testing, found them unrecognisable.

Choices

The heyday of Chitty Melaka has long past though many of their descendants are prominent in the communities which they have migrated too.

Their forefathers in Malacca made the decision to stay loyal to the Portuguese which cost them dearly, as they retreated, as the Dutch claimed victory.

The Dutch took away plum government and quasi government designations as well as preferential trading positions, and the Chitty Melakans were forced into unfamiliar territory as farmers and fishermen.

Undeterred, the bounty from the sea resulted in signature dishes such as Lauk Pindang Ikan (curry fish), prawns cooked in tamarind and pineapple, and squid and snail bathed in spicy sambal.

Even the humblest of shrimp, the udang gerago or grago, a Kristang word for krill, caught off the waters of Malacca is used liberally, as they punched way above their weight in umami when dried and toasted, fermented and preserved.

They also added textural interest to fritters and omelettes as well as dressings.

Grandmother stories

One of the most heart-warming stories from the “neneks” or grandmothers, who are the voices of the cookbook, is that of Merlin Pillay.

Merlin is a true Indian Peranakan beauty and was a stewardess with Singapore Airlines.

Her father fished both as a hobby and out of necessity, to add protein to their daily fare.

Merlin reminisces about how krill swarmed in local waters, such that her father, walking into the sea, would swoop them up in his billowing shirt and bring buckets home to be cooked into all sorts of dishes, including the krill fritters and omelettes, recipes of which are in the cookbook.

The Chitty Melakans did not come from farming stock, so vegetables which took little tending or could be foraged, formed a large part of their daily greens.

Fortunately, they can be bought as market stall holders in Tekka Market and Geylang Serai still get them from Malaysia.

The bitter undertones of Daun Turi (Sesbania grandiflora) are an acquired taste, but much relished as a near forgotten food.

The recipe in the cookbook has this spinach like green being cooked in toor dhal, the pigeon pea legume imported from India, giving a mellowness to the sharp bitterness while garlic, turmeric, cumin and tamarind have tempering effects.

The Heritage Food of the Peranakan Indians is truly a community effort.

Tanya with all the makings of a modern nenek-to-be, and her positive feisty “nothing can ever faze me spirit”, is resourceful and amazingly organised and tech-savvy.

She inspired and cajoled the home chefs into contributing their cherished family heirloom recipes. She thrusted onto me, audio recordings in Baba patois which I transcribed.

Other contributors allowed me into their kitchens, where I learned that using the batu giling, a rolling pestle on a granite mortar was very different from a batu lesong, which required more brute strength and rhythm than wrist skills.

Some had their sisters and children helping them along, deciphering recipes written in cookbooks, and thanking us, as familiar, but not often served dishes were recreated and taught.

Recipes for the masses

To ensure accuracy and replication, all the recipes were then moved to a professional test kitchen under the kind auspices of Clarence Ling, the owner of Allspice, and a heritage warrior.

There, led by professional cooks, we tailed the neneks who were used to the agak or guesstimate system, using their palms, thumbs, and noses as their weights and measures and translated them into grams and litres.

Our task was to ensure that even the most noob cook could whip up the dish, knowing that at each step of the way, their mentors are holding their hands, giving exact and clear instructions from the cookbook.

The public launch of the cookbook took place on 19 November 2023 at LaSalle, whose students also added a little surprise to the cookbook — a QR code to scan and see their animations of various highlights of the community.

The numbers of Indian Peranakans are certainly dwindling. Their numbers, unlike Chinese Peranakans are not sufficient to ensure intermarriage between them.

Many marry Indians and some, Chinese, with fewer and fewer continuing their customs or even cooking their dishes, and a landmark book such as this, created by the community, is a treasure indeed.

Jasmine Adams is the co-editor of Heritage Food of the Peranakan Indians (In a Chitty Melaka Kitchen). It is available at Allspice Institute (Blk 162 Bukit Merah Central #07-3545 Singapore 150162) and the Peranakan Indian (Chitty Melaka) Association Singapore. More info here.