One fascinating thing that arose from the Covid-19 pandemic is that it brought out the inner baker in many of us.

From sourdough bread to Minion-themed cookies, social media feeds in the past year have been bombarded by images of amateur bakers’ achievements — and disasters —made while being cooped up at home during lockdown.

My only baking accomplishment to date is a Nutella mug cake (“baked” via microwave at that).

If only baking skills could be inherited as my late mum was a wiz in making delicious traditional kueh such as love letters, pineapple tarts and kueh bangkit for Chinese New Year (CNY).

Making my own kueh bangkit one day, instead of buying them annually from supermarkets, is still a #lifegoal. But can an old dog learn new tricks? Should a novice attempt making traditional kueh?

Advertisement

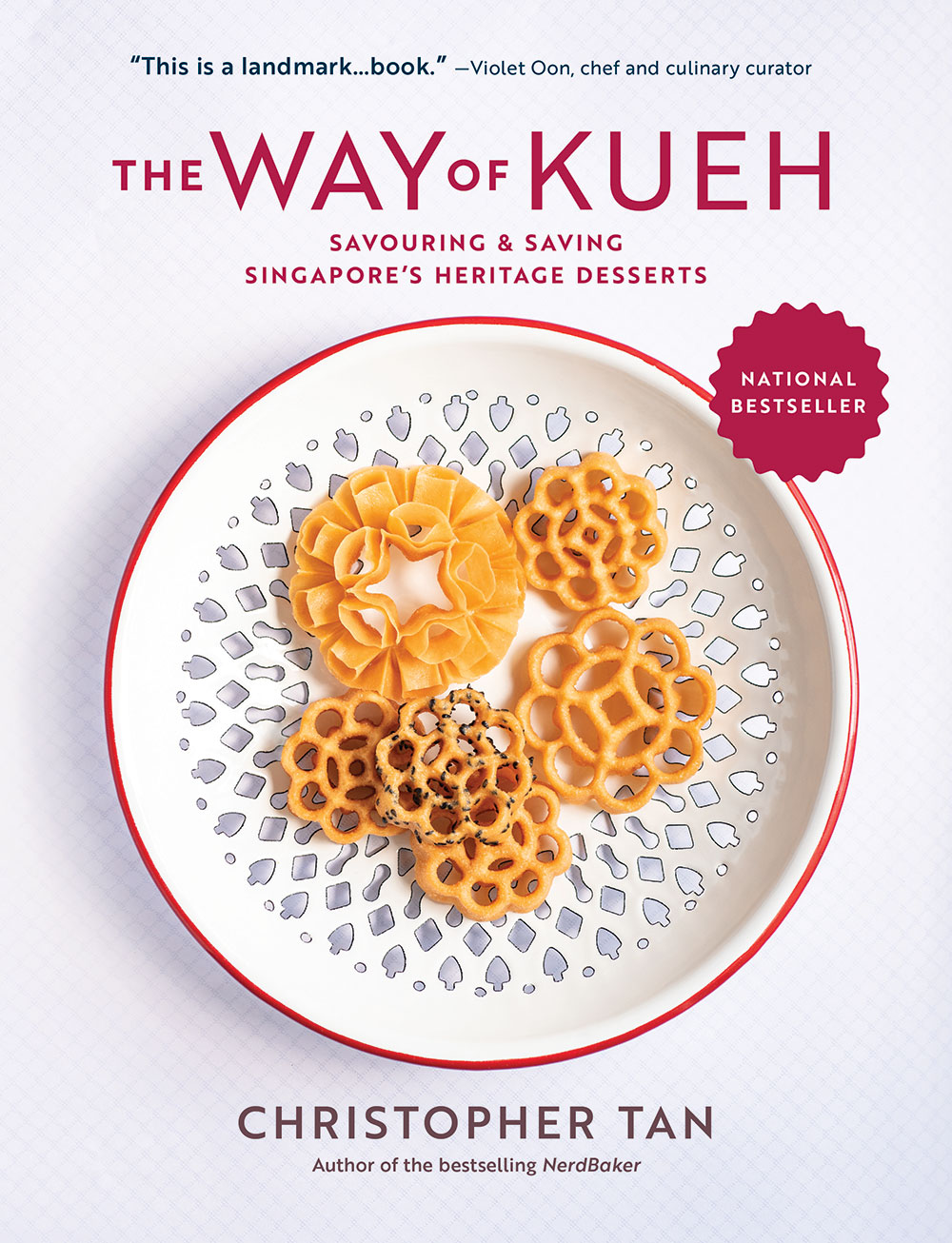

To find out, I approached Singaporean writer, cookbook author and culinary instructor Christopher Tan who wrote everything you need to know about kueh in his latest cookbook, The Way of Kueh.

The acclaimed culinary tome features 102 recipes — 98 traditional, four modern — which are Christopher’s interpretations of classic Singapore kuehs from the Chinese, Malay, Eurasian and Peranakan communities, as well as stunning photographs of kueh shot by the author himself.

It won Book of the Year and Best Illustrated Non-Fiction Title at the 2020 Singapore Book Awards.

Make Kueh While The Sun Shines

“I don’t think age is at all a hindrance to kueh-making,” says the 40-something Christopher, who grew up in a family of foodies.

“The most important things you need to bring to the kitchen table are your commitment and your attention to detail – this is true if you want to cook anything properly, not just kuehs. Be precise, be careful, keep calm and carry on!”

The affable food lover is all for encouraging people of all ages and skill levels to start making kueh at home to aid his mission in preserving and progressing Singapore kueh heritage before it disappears.

He explains, “Firstly and most importantly, kueh culture is worth holding on to simply because it is ours, and it is amazing! If we are food lovers, it would be a tragedy to disregard a food genre which is rich and diverse, and which has held so much meaning for us over so many centuries of history.”

As more people these days buy kuehs rather than making them at home, Christopher wants to drive home the fact that “home-made kuehs cooked with care and loving attention can be worlds better and much more delicious than commercial kuehs.”

He also reminds us that kueh-making in preparation for festivals or seasonal celebrations is also an activity over which families traditionally bonded.

As we lose the knowledge and habit of making kuehs at home, we are also losing these opportunities for family bonding, sharing and imparting family traditions, and leading members of the younger generation into a deeper appreciation of their personal, family and community heritage,

Christopher says:

"Going to the shops together to buy kueh is just not the same!"

This is The Way (of Kueh)

Masking the fact that this writer is indeed one of those who buy kueh from shops (blush), I asked the cookbook author of 13 books (and counting) which traditional kueh would he recommend our Silver Streak readers to start with if they are keen to try.

Christopher’s suggestion is ma tai koh, a classic Chinese steamed water chestnut cake that can be enjoyed all year round and “only gently sweet”. He also shares with us its “very simple recipe” (see below), which can also be found in The Way of Kueh.

Still, when it comes to choosing which kueh to make, as everyone has different preferences and skill levels, Christopher encourages readers to first “enjoy reading about kuehs–whether in my book or other books, maybe even their mum’s or grandma’s recipe notebook!–in order to discover which kuehs strike a chord in them.”

“Kueh-making should be ‘heartful’ as well as artful – it is always more fun and more inspiring to follow a recipe that you meaningfully connect with,” he concludes.

On that note, perhaps I should dig out mum’s kueh bangkit recipe first before attempting the ma tai koh…

Recipe by Christopher Tan

MA TAI KOH (water chestnut cake)

马蹄糕

This classic steamed kueh is enjoyed all year round, but is especially welcome at New Year – it is one of the trio of steamed kuehs which are a must for the Cantonese at CNY, the other two being radish cake (lor pak koh) and taro cake (wu tau koh). A very simple recipe and only gently sweet, ma tai koh showcases the flavour of fresh water chestnuts by embedding them in a softly springy, beautifully translucent jelly made with water chestnut starch.

Make sure to choose water chestnuts which are fat and very firm all over. Avoid those with mushy, spongy or soft spots. You will need about 300 to 350 grams fresh water chestnuts to get 200 grams of peeled chestnuts.

Water chestnut starch, coarse granules of dried water chestnut juice usually packaged in boxes, can be found at large supermarkets, at wet market dry goods stalls, and at baking supply shops.

Makes one 20 cm-square koh.

Ingredients

Starch solution

- 225 grams - water chestnut starch

- 600 grams - water

Syrup

- 650 grams - water

- 330 grams - yellow rock sugar or Chinese slab brown sugar (peen tong), crushed into small bits

- 6 to 8 - pandan leaves, cut into 1 cm shreds

- 200 grams - peeled fresh water chestnuts, thinly sliced or diced

- 1 tablespoon - oil or lard

- more oil or lard for greasing pan

Method

- Make the starch solution: combine starch and water in a bowl. Stir with a whisk or heavy spoon until the starch granules dissolve. This may take a few minutes. Cover bowl tightly and let the solution stand at room temperature for 20 to 30 minutes.

- Get your steamer ready. Very lightly grease with lard or oil the base and sides of a 20 cm square cake pan, at least 5 cm deep. Alternatively, you can instead use two loaf pans, each one about 10 cm wide by 20 cm long by 6 cm deep.

- Make the syrup: combine water, sugar and pandan in a pot, cover tightly and set over low heat. Stirring occasionally, cook until sugar completely dissolves and syrup just reaches a simmer.

- Strain syrup through a fine sieve into a clean pot. Discard pandan. Add water chestnuts and oil or lard to the syrup. Bring everything to a full but gentle boil over medium heat. Switch off the heat, cover the pot and let it sit for 2 to 3 minutes to cool down just slightly.

- Give starch solution a very good stir, then slowly pour it into the pot in a very thin stream while stirring constantly with a spatula. The mixture will quickly thicken, becoming like a cream soup. Turn on heat to low, then stir constantly with the spatula, scraping the pot sides and bottom, until the batter thickens into a creamy, custard-like paste – this will only take a couple of minutes.

- Scrape the paste into the greased cake pan or loaf pans, and spread it out evenly. Place pan in the steamer and steam for 20 to 25 minutes over medium heat, until ma tai koh is translucent and fully cooked.

- Transfer pan to a rack to cool. The koh will shrink and pull away from the pan sides as it cools.

- Unmould and slice to serve while the koh is still warm and soft. You can serve it plain, or roll it in lightly salted grated coconut. Keep leftovers in the fridge and finish them up within 2 days, the sooner the better.

- Alternatively, you can slice the chilled and firmed-up koh into slabs, sprinkle them with a little sugar, and pan-fry them with a little oil in a non-stick pan over medium-high heat, until they are lightly caramelised and browned in spots. Serve hot.

Resources:

The Way of Kueh is available at all good bookshops, such as Kinokuniya and Popular, as well as from online bookstores such as epigrambookshop.sg and booksactuallyshop.com.

Follow Christopher Tan on Instagram at @thewayofkueh. His cooking and baking classes can be found online at www.thekitchensociety.com.